Part of the remodeling of Britannia’s chart table area involved making a new section of floor, or to use its correct nautical term the cabin sole. After removing the old chart table I discovered the floor beneath was just rough plywood, unlike the remainder of the boat that was beautiful teak with maple strips. It was perhaps just as well, because in order to reposition the electrical distribution board, I had to chop this floor out completely to be able to re-route the wires underneath.

I naturally wanted any new floor to match the boats existing sole, so I scoured the web and other sources to find teak plywood flooring with white strips to match the floor pattern, but I was unable to locate the exact pattern anywhere. Britannia’s strips are 3/8” inch wide, but the nearest I could find were only 1/4” inch wide and also spaced differently, and I thought that using a different pattern would look like a “botch job.” The area was not large, only 54” inches long by 36” inches wide and needing 3/4” inch thick plywood to bring it level with the existing floor. I could have bought a 4’ foot by 8’ foot sheet of teak faced plywood, but it would have cost in excess of $400.00 with delivery costs, and it would still have no white strips. This would be an expensive section of floor with nearly half left over and nothing to use it for. I decided to try and copy the exact pattern myself, using a different approach.

I naturally wanted any new floor to match the boats existing sole, so I scoured the web and other sources to find teak plywood flooring with white strips to match the floor pattern, but I was unable to locate the exact pattern anywhere. Britannia’s strips are 3/8” inch wide, but the nearest I could find were only 1/4” inch wide and also spaced differently, and I thought that using a different pattern would look like a “botch job.” The area was not large, only 54” inches long by 36” inches wide and needing 3/4” inch thick plywood to bring it level with the existing floor. I could have bought a 4’ foot by 8’ foot sheet of teak faced plywood, but it would have cost in excess of $400.00 with delivery costs, and it would still have no white strips. This would be an expensive section of floor with nearly half left over and nothing to use it for. I decided to try and copy the exact pattern myself, using a different approach.

I bought the finest quality sheet of 4’ foot by 8’ foot by 3/4” inch thick smooth faced plywood I could find in our local hardware store. It cost $47.00 and they cut it to my rough size free of charge. It would have been difficult to shape such a cumbersome piece of plywood on the boat, so I made a template using sheets of art board and cut the plywood to shape with my table and jig saws in my garage. I took it back to the boat for a trial fit, but due to a very carefully made template the floor dropped in place perfectly. I also decided to incorporate a hatch in the new floor, to give direct access to three seacocks and a battery beneath.

I first painted all the edges and underside of the plywood with two coats of Interlux Primekote two-part epoxy primer, to seal the edges. Next I bought a 4’ foot by 8’ foot sheet of teak veneer. This was “quarter sawn,” meaning the grain is pretty straight along the 8’ length with no swirls or knots in the pattern. It was also Okoume wood backed, not paper like cheaper veneers, and much more suitable for flooring and flat sections, like bulkheads. I was advised to let the sheet acclimatize for 24 hours before trying to glue it to the plywood, to minimize any shrinkage or expansion once it was glued to the plywood.

I first painted all the edges and underside of the plywood with two coats of Interlux Primekote two-part epoxy primer, to seal the edges. Next I bought a 4’ foot by 8’ foot sheet of teak veneer. This was “quarter sawn,” meaning the grain is pretty straight along the 8’ length with no swirls or knots in the pattern. It was also Okoume wood backed, not paper like cheaper veneers, and much more suitable for flooring and flat sections, like bulkheads. I was advised to let the sheet acclimatize for 24 hours before trying to glue it to the plywood, to minimize any shrinkage or expansion once it was glued to the plywood.

When I first attempted veneering I was very unsure how to use these ultra thin sheets of real wood to cover damaged and rebuilt surfaces on my 35 year old boat. Veneering has a sort of mystique about it, that only master-carpenters are supposed to comprehend. In truth it is the easiest way to instantly improve timber, especially flat areas like bulkheads or floors. Veneer can easily be cut with scissors and glued with regular contact adhesive, and the new surface can then be treated the same as any other teak ply’, varnished, oiled or left untreated. The downside is; good quality veneer is expensive and my sheet cost $157.00 including shipping. But veneering is invariably cheaper than replacing complete panels of teak faced plywood.

Veneer also offers a great opportunity to be artistic. Just because you are veneering an old damaged teak panel doesn't mean you have to re-cover it with teak veneer. There are lots of beautiful wood veneers available with amazing patterns, like Walnut, Cherry, Mahogany, etc., all of which can enhance the decor of any boat.

Veneer also offers a great opportunity to be artistic. Just because you are veneering an old damaged teak panel doesn't mean you have to re-cover it with teak veneer. There are lots of beautiful wood veneers available with amazing patterns, like Walnut, Cherry, Mahogany, etc., all of which can enhance the decor of any boat.

Having said that veneering is not difficult, there are still a few tricks-of-the-trade worth noting. The easiest method to glue veneer to a large stiff substrate like plywood is to first copy the outline of the plywood shape on the underside of the veneer with a felt tip pen. Then with the veneer flat on a level surface, contact adhesive is then spread over just the outline drawn on the panel, and then also to plywood. I used Weldwood contact cement and poured it out of the tin, then spread it with a trowel having 1/8”inch serrations.

When the glue is nearly ready to bond, instead of trying to locate the large wobbly sheet of veneer accurately on top of the plywood, it is much easier to carefully lower the plywood on top of the veneer to the guidelines already drawn. The veneer can then be trimmed to remove it from the whole sheet, then turned over and smoothed, using a wide blade plasterers trowel. This works better than a roller because rollers are attached only at one end, so pressure is bound to be a little uneven. A wide blade trowel has the handle in the middle allowing even pressure over the whole blade as it is drawn along the veneer, from the center outwards. This squeezes all the air out and minimizes the chance of future bubbling of the veneer.

I trimmed the edges using my hand held router with a 1/2” inch straight cutter. The veneered board looked superb, but the job was only half done...

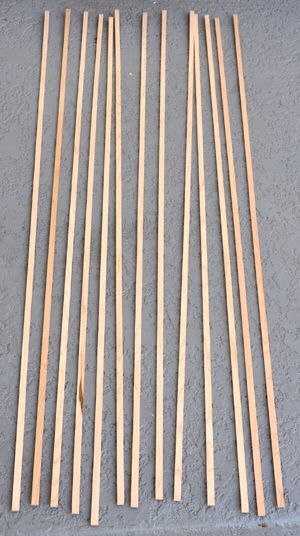

Now came the tricky bit. I somehow had to make thirteen 3/8” inch wide maple strips and set them into the teak veneered plywood. I found some maple in 48” inch x 3” inch x 1/8” inch thick at a specialist wood supplier in Orlando, Florida, where I lived.

Now came the tricky bit. I somehow had to make thirteen 3/8” inch wide maple strips and set them into the teak veneered plywood. I found some maple in 48” inch x 3” inch x 1/8” inch thick at a specialist wood supplier in Orlando, Florida, where I lived.

I bought a new 60 tooth 10” inch diameter carbide tipped blade for my bench saw that cuts thin timber very cleanly. Using the saw and its guide I carefully cut thirteen strips out of the sheet, each exactly 3/8” inch wide. This produced strips 3/8” x 1/8” inches to form the  inlaid floor strips.

inlaid floor strips.

The next process was to machine grooves in the teak board to take the strips. For this I used my small hand held router, fitted with a 3/8” inch plunge cutter that I set to produce a 1/8” inch deep groove. I taped the end of my vacuum hose to the router to suck shavings out from the tool and prevent them building up in the groove, and also see where I was cutting.

I placed the router level with the center of where I wanted the first groove then tightly clamped a stout straight timber board to the floorboard to act as a guide. After a little heart pounding for the first cut, it was then just a matter of slowly pushing the router along the guide and the result was a perfectly straight 3/8” inch wide groove down the length of the board. I repeated this process with a 2 1/8” inch space between each groove, until I had all the slots machined.

I used Titebond premium wood glue to bond the strips into the grooves, that only needed a tap with a mallet to seat them level with the veneer. I let the glue harden for 24 hours, then trimmed the overhangs and edged the hatch with 1/4” inch wide teak strips, and also fitted a brass lifting handle to match the rest of the hatches. Then I lightly sanded the whole sheet and hatch with my belt sander with 120 grit to smooth the Maple to the level of the veneer. These 1/8” inch deep strips will be very wear resistant because the strips in the existing cabin sole are only the same thickness as the teak veneer, and easily chipped if you are not careful.

I rolled on a first coat of Cetol clear marine wood varnish thinned with mineral spirits, then two unthinned coats without sanding between coats, like I did when I renovated the boat floors. Not only does this produce a thicker coverage for floor protection, but also produces a non-slip surface because the unsanded wood leaves a slightly coarse finish. This can hardly be felt even with bare feet, yet it also results in a glossy finish.

I then decided to glue a layer of thermal insulation to the underside of the board to minimize heat coming through from the engine area. For this I used 2” thick Rmax Thermasheath foam insulation board with aluminum foil on one face. This has an insulation rating of R6, that is the highest available for this thickness of foam. I glued it to the underneath of the floor using Liquid Nails construction adhesive, that does not melt the foam. The new floor was a perfect match to the remainder of the saloon and the Maple strips mated perfectly with the others. I still had work to do with the wires under the floor, so I didn't fasten it down until that was finished. I then screwed it down and filled the countersunk holes with teak plugs, Job done!

The whole project was a back-aching sort of job, with a lot of kneeling down and sawing, but well worth the effort to match the existing sole. I'm sure it would not have looked right had I used an odd-size ready made teak flooring. I even had a big piece of veneer left over, that I used to repair other parts of Britannia’s teak.