Following an unsuccessful attempt In January 2022 to move Britannia from Florida to the New Bern, Pamlico Sound area of North Carolina where we ha moved to, I was now ready for another crack at the 530-mile passage. It was then late April 2022

Pamlico Sound is a very large inland sea, protected from the Atlantic rollers by a string of outer banks, some with town on them with famous names like Kitty Hawk (of Wright brothers fame), and quaint seaside villages like Ocracoke, (of the pirate Blackbeard notoriety), and Cape Hatteras. Pamlico sound nc - Bing The sailing waters are about 60 miles long (E to W) and 20 or so miles wide (N to S), with many large tributary rivers and old colonial towns like Bath and Washington, (not DC of course) to explore. The Sound is also steeped in pirate history and  where the Englishman known as Blackbeard roamed and finally met his end. The Intracoastal waterway also passed through the sound, so many transit sailors will know the area.

where the Englishman known as Blackbeard roamed and finally met his end. The Intracoastal waterway also passed through the sound, so many transit sailors will know the area.

We had bought a house in Fairfield Harbour, (that’s not a typo), halfway up the Neuse River towards New Bern. Fairfield’s man-made harbor has a large central lagoon with finger canals, a bit like Fort Lauderdale, and many houses have their own docks, some with very expensive looking boats at the bottom of the garden. At this point, the Neuse is a mile wide and feeds the western end of Pamlico Sound.

TIME TO LEAVE.

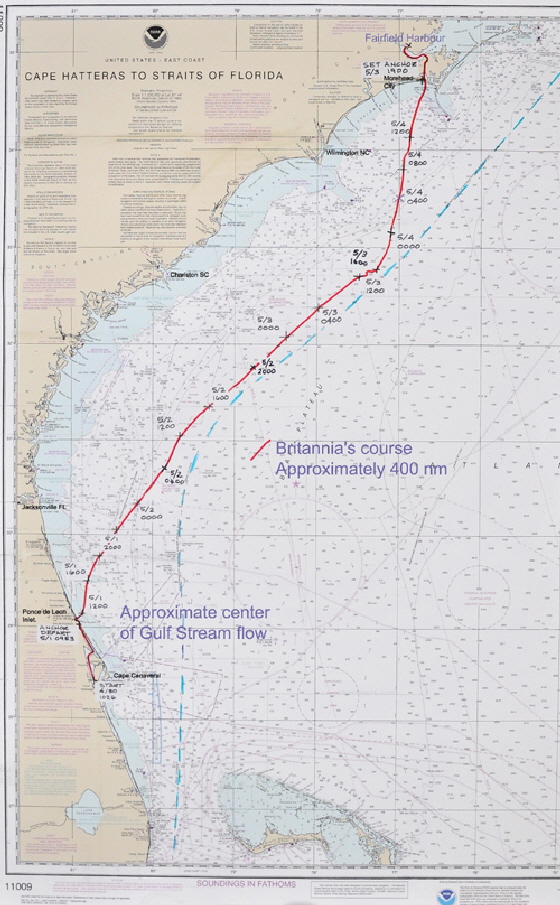

Britannia was moored at Cape Canaveral, Florida, and needed to be sailed up the Eastern seaboard to the Beaufort Morehead City inlet, then up a river to the Pamlico and a marina slip I had leased inside the lagoon. It was not practical to bring her up the intracoastal waterway because of her 6’ 6” inch draft. It was not a long passage compared to some of the ocean voyages we have made, and it could also be an easy trip if we timed it right. We were looking for southerly winds to fill the fore-course squaresail, and also hitch a ride on the famous Gulf Stream current that flows up the Eastern Seaboard of the USA.

The Gulf Stream originates in the Gulf of Mexico, where warm Caribbean water flows north and start to circulate in what is called a loop current. It then squeezes between Florida, Cuba, and the Bahamas and expands to an amazing 60 miles wide and some 4000 feet deep river in the Atlantic Ocean. It is the largest of the world's currents and transports nearly four billion cubic feet of water per second! more than all the worlds rivers combined. It is also warmer than the Atlantic waters through which it passes by some six degrees. (Source: The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration)

Seafarers have known about the Gulf Stream for a long time. In 1513 Spanish explorer Ponce De Leon noted there was a strong current running north, and Spanish treasure ships used the stream to speed their passage across the Atlantic, hence it also became the domain of pirates and many shipwrecks. History was indeed made in these waters.

Unfortunately from January until April the winds had been predominantly from the north, with strong fronts swinging across Florida, bringing torrential rain and 20 to 30 knot northerly winds. This created wind-over-current in the Gulf Stream and horrendous breaking waves. I can't say I blame Britannia for not wanting to brave that passage, and happy enough to wait in her snug marina dock. But at $675 a month I needed her out of it and I frequently became red-eyed looking at weather projections on the web. I had subscribed to Chris Parker’s marine weather forecasting service and he sent regular weather update, with possible windows for the trip north. Chris will be known to ocean sailors for his worldwide meteorological forecasting, www.Chrisparker.com, and I cannot speak highly enough of his service.

As sailors of small boats know, (sometimes to their cost), waiting for the right weather is the prudent thing to do and a calendar is the worst thing you can have on a sailboat. That's all very well, but I needed a crew of at least two for night watches and sail handling and that's not so easy to arrange when they have jobs and other complications like wives, and I couldn't be sure when we would be leaving anyway. So we waited and waited and waited, sometimes missing a possible window for one reason or another.

We had moved house by this time and for three months the weather remained cruelly changeable during which my wife Kati and I made three 730 mile trips, (each way), from New Bern to check on Britannia in Cpat Canaveral. Finally, at the end of April a four-day window looked like we could expect easterly, then southeasterly winds out of the Atlantic and my crew was also available. We had to go now!

We had moved house by this time and for three months the weather remained cruelly changeable during which my wife Kati and I made three 730 mile trips, (each way), from New Bern to check on Britannia in Cpat Canaveral. Finally, at the end of April a four-day window looked like we could expect easterly, then southeasterly winds out of the Atlantic and my crew was also available. We had to go now!

THE CREW

My first mate was Bob Snell, a very experienced yachtsman who made the attempt with me to break free of Florida a few months earlier. This ended miserably in a passage of no more than 30 miles, when a diesel fuel pipe rupture forced us to abort the trip and even have a tow for the first time in my sailing life. Bob's girlfriend Lisa Averill had little experience of ocean sailing or night passages and came as the cook.

Another very experienced yachtsman was Kevin Derr, who operates a Tow-boat USA rescue boat and who I met for the first time when he came to our rescue at 3 am that dark blustery night on our first attempt to make the passage and I was very pleased to have Kevin as a member of the team. Kevin's girlfriend Kim Wielgus came along to gain experience for her captain's license application. She had sailed on a few sailboats but not one as complicated as Britannia’s rig. I asked Kim if she would act as the photographer for the images I would need to submit

Another very experienced yachtsman was Kevin Derr, who operates a Tow-boat USA rescue boat and who I met for the first time when he came to our rescue at 3 am that dark blustery night on our first attempt to make the passage and I was very pleased to have Kevin as a member of the team. Kevin's girlfriend Kim Wielgus came along to gain experience for her captain's license application. She had sailed on a few sailboats but not one as complicated as Britannia’s rig. I asked Kim if she would act as the photographer for the images I would need to submit  this story to the boating magazines I write for. The shots are all Kim’s with the exception of those accredited to others.

this story to the boating magazines I write for. The shots are all Kim’s with the exception of those accredited to others.

My wife was unable to come on the trip because of other commitments, but she provisioned Britannia with over $400 worth of vittles and drinks from a list provided by Lisa, including 14 frozen dinners that could be easily prepared in the convection microwave.

THE PLAN

The night before departure we had a get-together in Britannia's saloon, where I asked each person to describe their sailing history, so others would have an idea of their experience. I also explained the intended plan.

The night before departure we had a get-together in Britannia's saloon, where I asked each person to describe their sailing history, so others would have an idea of their experience. I also explained the intended plan.

Bob and I decided we would do the same as last time. Motor-sail north on the Intracoastal Waterway to New Smyrna Beach. This was a distance of only 50 miles and would be a good test of the repairs I had made since the last disastrous jaunt. It would also allow the crew to become familiar with each other and the boat, then all being well we would enter the Atlantic Ocean at Ponce inlet.

During this short hop the engine started to overheat and we had to slow to keep the temperature down. We anchored at New Smyrna for the night where we investigated the problem and found a leak in the header tank filler flange that would not allow the engine to pressurize properly. This was sealed with a new gasket that we hoped would fix the problem.

Unfortunately the new gasket did not cure the overheating, but we decided to proceed anyway. We then spent the whole passage nursing the engine with maximum revolutions around only 1300 rpm, otherwise the temperature would rise excessively and we would have to throttle back, or shut the motor down until it cooled. We estimated that this added almost a day to the passage. However, being propelled by the Gulf Stream and fair winds made up for some loss of engine power. Another thing the cranky engine made us do, was actually sail the boat!

ROLLING ALONG.

The inlet through which we entered the Atlantic is called Ponce Inlet and the lighthouse is Ponce De Leon Light. If we could ride the Stream all the way north it would give us a very nice push and we could then hop off at Beaufort inlet. The current was reported to be running at between 2 and 3 knots. Not a bad hoist if we could catch it. After a leisurely departure we entered the Atlantic Ocean at 0953 on 1st May 2022 to meet a rolling sea from the east and an easterly wind at about 15-20 knots as Chris Parker had predicted. We bore away on 015 degrees and rolled out the jib, fore staysail, and mainsail. All the sails on Britannia are roller furled, controlled from each side of the companionway from the rope decks. The sails steadied the boat somewhat, but we still rolled heavily in some of the easterly swells,

The inlet through which we entered the Atlantic is called Ponce Inlet and the lighthouse is Ponce De Leon Light. If we could ride the Stream all the way north it would give us a very nice push and we could then hop off at Beaufort inlet. The current was reported to be running at between 2 and 3 knots. Not a bad hoist if we could catch it. After a leisurely departure we entered the Atlantic Ocean at 0953 on 1st May 2022 to meet a rolling sea from the east and an easterly wind at about 15-20 knots as Chris Parker had predicted. We bore away on 015 degrees and rolled out the jib, fore staysail, and mainsail. All the sails on Britannia are roller furled, controlled from each side of the companionway from the rope decks. The sails steadied the boat somewhat, but we still rolled heavily in some of the easterly swells,  that remained with us for the whole passage.

that remained with us for the whole passage.

It was late afternoon before the wind began to veer and we were able to alter course to 045 degrees to meet our rendezvous with the Gulf Stream about 30 miles to the east. Unfortunately this meant we would not enter it until well after dark and I was disappointed not to be able to see our moving staircase, that is usually quite distinguishable due to the sea color change, from grey-green to a perfect blue. Still, we had a spectacular sunset that only a sunset at sea can give.

What did become amazingly apparent as we entered the edge of the stream about midnight was the steady increase in our speed. Entering the Gulf Stream is a bit like driving down a slip-road onto an interstate, as you slide into the inside lane then accelerate in the traffic flow. As we sailed further into the stream Britannia increased speed markedly, from 6.5 knots to finally 9 and occasionally 10 over the ground, as though we had just hoisted a spinnaker or large Genoa. We were now plowing along with a rushing bow wave and a long florescent wake. Britannia had a bone in her teeth.

What did become amazingly apparent as we entered the edge of the stream about midnight was the steady increase in our speed. Entering the Gulf Stream is a bit like driving down a slip-road onto an interstate, as you slide into the inside lane then accelerate in the traffic flow. As we sailed further into the stream Britannia increased speed markedly, from 6.5 knots to finally 9 and occasionally 10 over the ground, as though we had just hoisted a spinnaker or large Genoa. We were now plowing along with a rushing bow wave and a long florescent wake. Britannia had a bone in her teeth.

A unique phenomenon of ocean passage making is the night sky, unencumbered by land glare, and our first night was spectacular including the full panoply of the Milky Way. Another thing landlubbers never see is moon rise with its silvery path from the horizon to the boat. as spectacular as any sunset. There were lots of wows and  camera clicking, but of course no printable photos due to the rolling of the ship.

camera clicking, but of course no printable photos due to the rolling of the ship.

In the morning, as we sailed deeper into the wide current we began to see many large multi-colored tropical fish similar to Dolphin, (Mahi Mahi), swimming alongside. We could almost scoop them up, so where was the fishing tackle when we needed it? The sea was a perfect blue and paint manufacturers should name a color for it ‘Gulfstream Blue.’

The wind remained steady from the southeast so I unrolled the between mast staysail, for which a schooner is so suited. It is set between the masts a bit like a mizzen staysail on a ketch, and this sail further increased out speed.

The wind remained steady from the southeast so I unrolled the between mast staysail, for which a schooner is so suited. It is set between the masts a bit like a mizzen staysail on a ketch, and this sail further increased out speed.

As the crew became accustomed to the motion we all settled down to the routine of a small boat on a very large ocean. Our course, or rather the course dictated by the Gulf Stream meant we were heading away from land to be 120 miles at the widest point on a direct course for Beaufort Inlet, and no way were we going to lose that fantastic escalator. Of course, as every experienced ocean voyager knows it was just too good to last.

We had been running the motor slowly to maintain the batteries, but suddenly it spluttered to a halt and Kevin and Bob set about finding out why and quickly discovered that the starboard fuel tank had run dry. We had been running off both tanks or so I thought, but no fuel had been coming out of the port tank because the discharge pipe was found to be completely blocked. Britannia had been rolling heavily so it was probable that sediment had been disturbed in the tanks and blocked the pipe.

I had complete confidence in my two mechanics to get the motor going again, so I decided to leave them to it. I had my own problems anyway, trying to keep the boat moving in a declining wind. At one point we appeared to be only moving forward at the speed of the current and it was Bob who later coined the phrase, “Becalmed at three knots.”

I had complete confidence in my two mechanics to get the motor going again, so I decided to leave them to it. I had my own problems anyway, trying to keep the boat moving in a declining wind. At one point we appeared to be only moving forward at the speed of the current and it was Bob who later coined the phrase, “Becalmed at three knots.”

The lads reconnected the port tank to the engine line with a separate hose that allowed fuel to be drawn from that tank. All the filters were changed, because it was a fair bet that a lot of tank sludge would have been drawn into them in the dying moments of the engine. The new filters then had to be primed and the engine bled, which took hours to get the motor to start again. But start it did.

The weather had been kind to us thus far, but now a new obstacle appeared ahead on the horizon in the unmistakable sign of a large thunderhead squall. These are prevalent in the warm Gulf Stream waters and many are small and not serious hazards, but this one was gigantic. It looked like miles across and to be avoided at all costs, but we were not at all sure which way it was moving if at all. The consensus was that it would likely be traveling eastward so we altered our course to the northwest. As we got closer water spouts could be seen within the colossus, and these tornado-like formations have been known to sink bigger ships than ours. However, everyone became less anxious as we slowly passed to the west of the storm, and were then able to return to our proper course. I privately wondered what would have happened if it had not been spotted during the night and we had run straight into it? But this was why I insisted that one of our experienced members be on watch at all times throughout the night.

The weather had been kind to us thus far, but now a new obstacle appeared ahead on the horizon in the unmistakable sign of a large thunderhead squall. These are prevalent in the warm Gulf Stream waters and many are small and not serious hazards, but this one was gigantic. It looked like miles across and to be avoided at all costs, but we were not at all sure which way it was moving if at all. The consensus was that it would likely be traveling eastward so we altered our course to the northwest. As we got closer water spouts could be seen within the colossus, and these tornado-like formations have been known to sink bigger ships than ours. However, everyone became less anxious as we slowly passed to the west of the storm, and were then able to return to our proper course. I privately wondered what would have happened if it had not been spotted during the night and we had run straight into it? But this was why I insisted that one of our experienced members be on watch at all times throughout the night.

The following morning the wind veered more to the south onto our stern and the head sails began to constantly shake with the swell. It was time to unfurl the fore-course squaresail I had invented, that hung from Britannia’s foremast and was designed for exactly this kind of wind. It is a 350’ square foot sail that rolls up and down inside its hollow yard like a blind. However, as I looked up at the yard I immediately knew something was wrong because it was swaying slightly from side to side. This should have been impossible since it was attached to the mast at its gooseneck, except that it now appeared it was just hanging loosely by its hoist and lifts. With the boat rolling so much I was not about to go up the mast to investigate or allow anyone else to do so. This left two options, lower the yard and lash it securely to the mast, or unfurl the sail and let it fly, using the hoist, lifts and braces to hold it steady. I chose the latter and the sail quickly steadied pushing us along handsomely.

The following morning the wind veered more to the south onto our stern and the head sails began to constantly shake with the swell. It was time to unfurl the fore-course squaresail I had invented, that hung from Britannia’s foremast and was designed for exactly this kind of wind. It is a 350’ square foot sail that rolls up and down inside its hollow yard like a blind. However, as I looked up at the yard I immediately knew something was wrong because it was swaying slightly from side to side. This should have been impossible since it was attached to the mast at its gooseneck, except that it now appeared it was just hanging loosely by its hoist and lifts. With the boat rolling so much I was not about to go up the mast to investigate or allow anyone else to do so. This left two options, lower the yard and lash it securely to the mast, or unfurl the sail and let it fly, using the hoist, lifts and braces to hold it steady. I chose the latter and the sail quickly steadied pushing us along handsomely.

Our third night at sea passed with little incident, except that the 6.5 Kw Kabuto generator suddenly decided not to run for more than ten minutes before stopping, when we had to wait for it to cool down. This was only just time to cook a frozen dinner - if you were quick. Luckily there were other food options and nobody starved.

We were still rolling from the easterly swell and as if knowing this would be our last night one hefty wave rolled me completely out of my saloon settee berth and I found myself on the cabin floor, pillow and all. I knew I couldn't fall any further so that's where I stayed. I really must add lee clothes to my list(s).

As we began to close the land, cell phone coverage resumed at 15 miles and mobile phones appeared as if from nowhere. I had a hard time finding a willing hand to help run the ship and could have fallen overboard and nobody would have noticed. It seemed like half of America was wondering where we were, but we were now heading home and families and friends needed reassurance that we were okay.

There was still one more trial in store as we approached the wide Beaufort inlet. On trying to wind the in-mast mainsail into its slot a loose halyard found its way into the fold and jammed the sail. I had to turn Britannia round into the heavy following swell while the crew unwound the sail and pulled the halyard out, then wound it back in. This was achieved with skill and careful precision and we motored slowly into a calm spot on the Moorhead City side of the inlet, and thankfully to everyone, dropped the hook at 1900 on 4th May 2022.

There was still one more trial in store as we approached the wide Beaufort inlet. On trying to wind the in-mast mainsail into its slot a loose halyard found its way into the fold and jammed the sail. I had to turn Britannia round into the heavy following swell while the crew unwound the sail and pulled the halyard out, then wound it back in. This was achieved with skill and careful precision and we motored slowly into a calm spot on the Moorhead City side of the inlet, and thankfully to everyone, dropped the hook at 1900 on 4th May 2022.

The sun was below the yard so it didn't take long for a few of the crew to consume half a bottle of Irish whiskey, (I won't say who, but one of their names begins with R), to celebrate our safe landfall.

The sun was below the yard so it didn't take long for a few of the crew to consume half a bottle of Irish whiskey, (I won't say who, but one of their names begins with R), to celebrate our safe landfall.

In the morning we weighed, (slowly, due to a few hangovers), and set off up Adam's Creek that connects Beaufort inlet to Pamlico Sound. This is some creek! and more like a wide river for most of the way with many stylish houses and boat docks on both banks. It was an emotional moment for me to finally emerge into the Neuse River-Pamlico Sound, and feel a welcoming wind from the east to greet me. We even set a jib and the ˜tweenmast staysail to carry us the last 15 miles to the entrance to Fairfield Harbour and Britannia’s mooring. We entered the inner lagoon at 1500 on 5th May 2022.

It was an emotional moment for me to finally emerge into the Neuse River-Pamlico Sound, and feel a welcoming wind from the east to greet me. We even set a jib and the ˜tweenmast staysail to carry us the last 15 miles to the entrance to Fairfield Harbour and Britannia’s mooring. We entered the inner lagoon at 1500 on 5th May 2022.

I would like to thank all the crew for their help in bringing Britannia to her new home. Particularly the sterling work Bob and Kevin did with the engine failure. Also Kevin’s superb navigation and the lovely photographs taken by Kim. There were many frustrating weeks when I was unable to coordinate a crew with a weather window, when Kati and I considered bringing the boat up on our own but I'm pleased we didn't. Oh! and thanks also to the Gulf Stream, without which we would probably still be out there.

Needless to say, I have some work to do before the first exploration of our new sailing grounds. Poor old Perky Perkin’s cooling water pipes proved to be almost completely clogged to the point that I was amazed he worked at all. These had to be completely dismantled and cleaned out from the water inlet to the exhaust, including the heat exchanger, inlet and exhaust manifolds and both the seawater and freshwater pumps. I can't believe all that silt came from the grounding in the Intracoastal on our first attempt to make the passage. It had probably built up over years. from other lesser groundings

A split-pin on the yard gooseneck had sheared, probably due to the heavy rolling and caused the connection to part. I only had to replace a spring latch to be able to re-hoist the yard. The trouble was I had to wait for it to come from France.

I repaired the fuel problem by installing a new pipe and it is now working fine. I am planing to clean both tanks and polish the remaining fuel.

Following is an except from a new book about climate change pertaining to the Gulf Stream: Hothouse Earth, an Inhabitants Guide, by Bill McGuire is published by Icon Books, £9.99.

Losing the Gulf Stream as the ice caps melt, the resulting cold water pouring from the Arctic threatens to block or divert the gulf stream that carries a prodigious amount of heat from the tropics to the seas around Europe. Signs now suggest the Gulf Stream is already weakening and could shut down completely before the end of the century, triggering powerful winter storms over Europe.

Food for thought indeed.