Freshwater pipes can be seen connected to lots of boats in marinas, especially liveaboards. A hose is connected from a water valve on the dock, to a pressure reducing inlet on the boat that reduces municipal water pressure, usually around 60lbs to about 35lbs. This pressurizes all the water outlets on the boat and has advantages: it gives constant pressure at all outlets; it is silent and there are no noisy electric pumps running; it is a more even and usually stronger flow than a pulsating pressure pump for say, a shower; there is no drain on the batteries; water comes in fresh from the shore instead of the tanks, that might have been there for a long time.

Freshwater pipes can be seen connected to lots of boats in marinas, especially liveaboards. A hose is connected from a water valve on the dock, to a pressure reducing inlet on the boat that reduces municipal water pressure, usually around 60lbs to about 35lbs. This pressurizes all the water outlets on the boat and has advantages: it gives constant pressure at all outlets; it is silent and there are no noisy electric pumps running; it is a more even and usually stronger flow than a pulsating pressure pump for say, a shower; there is no drain on the batteries; water comes in fresh from the shore instead of the tanks, that might have been there for a long time.

My 50’ foot schooner Britannia had this system installed by the boat makers. The ½” inch diameter plastic water pipes were therefore as old as the boat, circa 1977, with a maze of connectors all in a tangled mess in the bottom of the bilge. I was constantly repairing or replacing sections that leaked, or which cracked and that the automatic bilge pump would always alert me to, by switching itself on. I was very aware the whole system needed upgrading, but so did a lot of other things. We didn't live aboard and the pipes were only pressurized when we were aboard, so I fixed leaks as they broke.

Britannia is a long keeler with an abnormally large bilge that runs 26’ feet under the floorboards and is 4’ 6” inches deep to the keelson below. This cavernous area contained the Perkins main engine; a Kubota generator; a 22 gallon water heater; 10 batteries and 8 electric pumps. It is an extremely large area that I call the machinery bay. I actually built a wooden ladder to climb up and down in safety.

Britannia is a long keeler with an abnormally large bilge that runs 26’ feet under the floorboards and is 4’ 6” inches deep to the keelson below. This cavernous area contained the Perkins main engine; a Kubota generator; a 22 gallon water heater; 10 batteries and 8 electric pumps. It is an extremely large area that I call the machinery bay. I actually built a wooden ladder to climb up and down in safety.

It was always my practice to turn the water off at the dock whenever I left the boat, even for a short time, and when I left it for days I would disconnect the hose at the shore valve. Except for this one time when I forgot. But I was only in town for a few hours... Upon returning to the boat I immediately noticed the air conditioning outflow had stopped, which was unusual. In the saloon I lifted a floorboard to check the AC water circulation pump, and received the shock of my long and varied sailing life! Water was sloshing about 12 inches below the floor beams. I don't remember my actual words, but they definitely couldn't be printed here.

I confess I totally freaked out, and didn't even think to test the water to see if it was fresh or saltwater, which would have immediately pointed me to a possible source of the flooding. Instead I dashed to the Marina office, only to be told their portable pump was “waiting for parts,” and it had been waiting for at least four months to my knowledge. I ran to the engineering shop next door and implored their help to “man the pumps,” and Jeff Belford, the owner of Boaters Edge, (boatersedge.net) came over immediately trundling a massive gas engine pump, with a very long 3” inch diameter hose attached. After some heart stopping moments it roared into life and I shoved the suction end into the water that still seemed to be rising. The pump soon started to reduce the level, that was well over my eight brand-new batteries, all the pumps and halfway up the engine. The boat seemed to be down on her marks about twelve inches, and that's some water in a bilge the size of Britannia’s!

I confess I totally freaked out, and didn't even think to test the water to see if it was fresh or saltwater, which would have immediately pointed me to a possible source of the flooding. Instead I dashed to the Marina office, only to be told their portable pump was “waiting for parts,” and it had been waiting for at least four months to my knowledge. I ran to the engineering shop next door and implored their help to “man the pumps,” and Jeff Belford, the owner of Boaters Edge, (boatersedge.net) came over immediately trundling a massive gas engine pump, with a very long 3” inch diameter hose attached. After some heart stopping moments it roared into life and I shoved the suction end into the water that still seemed to be rising. The pump soon started to reduce the level, that was well over my eight brand-new batteries, all the pumps and halfway up the engine. The boat seemed to be down on her marks about twelve inches, and that's some water in a bilge the size of Britannia’s!

As the powerful pump began to make its mark, cooler thoughts began to prevail and I tested the water with a finger. It was definitely freshwater and that was when I realized the dock hose was still switched on. A crowd had gathered by this time and I was embarrassed to ask someone to close the tap. It seemed like an eternity before the water receded, to expose first the batteries then the various pumps and motors that operate all the boats systems.

In total there are four electric motors on the electric toilets waste systems; a large 120-volt air conditioning circulation pump; a big water pressure pump; a deck-wash pump and the generator electric fuel pump. That's eight electric motors, not to mention the large starter motors and their solenoids for the main engine and diesel generator. All these had been completely submerged including the main engine transmission. As the water receded below the battery tops the twin bilge pumps miraculously started up and did their best to help the big pump. They had undoubtedly been overwhelmed with the inflow then shorted out as water covered the batteries.

Even after the water was eventually pumped out I remained in a state of shock. Worries about the damage and cost overwhelmed me, especially since much of the equipment was new, and still under warranty: like $1000 worth of new batteries; $2,850 for a new generator and many of the pumps. Thoughts of what was now swilling inside both the engine and generator made me feel physically sick, and I found it difficult to formulate a list of priorities in my mind.

I began by unscrewing each battery filler plug and testing the specific gravity with a hydrometer. They were normal and the rims of the plugs were dry so it looked like no water had entered, and freshwater might not have done serious damage anyway. I withdrew the main engine dipstick that showed a layer of milky oil, as did the generator engine. Water could also be seen up to the filler neck in the gearbox. I needed to get it all out urgently!

I opened the engine oil drain plug and the catch-pan filled with a creamy mixture of oil and water. The generator contained the same mixture that I drained into a bucket. The transmission drain plug was completely inaccessible under the gearbox so I used a 1/4” inch neoprene tube and a small portable impeller pump to suck the oil out into a bucket.

I opened the engine oil drain plug and the catch-pan filled with a creamy mixture of oil and water. The generator contained the same mixture that I drained into a bucket. The transmission drain plug was completely inaccessible under the gearbox so I used a 1/4” inch neoprene tube and a small portable impeller pump to suck the oil out into a bucket.

I knew I needed to start the engines as quickly as possible, always assuming the starters worked. I rushed to a nearby garage and bought five gallons of their cheapest oil. There was little point in buying good quality because I knew one oil change would not be enough to eliminate the water. and I had plenty of spare filters. I also bought a hair drier in the hope of drying out some of the electrics.

The 4” inch diameter engine room blowers had not been submerged so I switched them on to start a fast airflow throughout the whole machinery bay. By now it was late evening and the equipment was not the only thing completely drained. I simply couldn't face trying to start the engines. so I had a few beers and went to bed. but I did not sleep well. At about 6 am I began refilling the diesel engines and transmission with new oil. I drained them once more then refilled them again along with fitting new filters. By this time both engines had 24 hours to drain any water into their pans. I used the hair drier to warm up the starter motor and it was now the moment of truth. I said a little prayer as I pressed the starter button. and trusty old “Perky” burst into life immediately. Wow!! I left it running to warm up on tickover and notices that steam was coming out of the exhaust. as well as a good flow of raw water.

Before trying to start the Kubota diesel on the generator I disconnected the electrics in the control box. This prevented the generator from actually making electricity. yet it allowed the rotor to spin and clear any water inside, again that is assuming the engine fired. I heated the starter the same way and pressed the starter button. The motor turned over sluggishly then fired. Yippee! How on earth these two starters worked, having been completely submerged I have no idea, but I was not complaining.

I knew it would be beneficial if I could get some dry air into the equipment bay, so the next items to start were the two air conditioners. The 120-volt pump that circulates seawater through the AC units is an open windings type motor, so I used the hair drier to blow hot air into it for ten minutes. The actual AC units are mounted high and were not flooded. As I started one air conditioner I heard the pump start and a quick inspection of the overflow outside told me that water was being pumped through both units. Another lucky break!

Everything else needed individual inspection, so I decided to start forward and work aft. This began with the electric pump for the deck-wash. It had been submerged and refused to start. That was a low priority at the moment and later I dismantled it and cleaned the commutator and brushes, when it sprang to life as though nothing had happened.

Everything else needed individual inspection, so I decided to start forward and work aft. This began with the electric pump for the deck-wash. It had been submerged and refused to start. That was a low priority at the moment and later I dismantled it and cleaned the commutator and brushes, when it sprang to life as though nothing had happened.

The dedicated windlass battery had not been submerged and the windlass worked fine. Some spare mooring ropes stowed below were saturated and were dragged on deck, where the Florida sun soon dried them out.

The water pressure pump also started up, drawing water from the two tanks to pressurize the system and that was when I spotted the cause for the flooding. A water pipe had blown out of its connector and the shore water had continued to flood the boat. These were compression fittings held together with a screw-on plastic cap. I repaired the joint and the system pressurized normally from the pump. That old system definitely had to go!

I was on my own all this time and the effort took two full days, but after a third oil change in the engine and with all other systems running again, I felt I had it all back to normal, after a very very close call indeed. Seeing your boat full of water is frightening, even if you are tied to a dock. Without a doubt if I had not returned and caught it when I did she would have eventually gone down. The dockmaster later told me he had seen two unattended boats sink in this way.

A PREVENTIVE REMEDY.

I don't know how many years this episode has taken off my life, but the question now was: how to prevent it ever happening again? There was no guarantee against another pipe failure, or me forgetting to switch off the shore water when I left the boat, although I think this highly unlikely after what I had just been through. It had been indelibly impressed in my brain.

The obvious thing that was suggested by several well meaning sailing mates was not to use a shore water supply at all, and draw from the tanks, refilling them as needed. This would certainly prevent a recurrence, except it would drain the tanks. However, the same might be said about the shore electrical connections that everyone uses without a second thought, for battery charging, etc., yet that has been the cause of many a boat fire.

My wife and I very much liked all the benefits of a shore water supply, when we stayed on the boat for weekends. So it was more a question of how to make it as fail-safe and as idiot proof, (that would be for me) as possible. The first obvious thing was to re-plumb the whole boat with new pipes and modern connectors, to stop the pipes breaking at all.

I found a system at my local hardware store called PEX. It is used to plumb houses and buildings instead of using expensive copper pipe. The connectors are guaranteed not to leak or blow out of the pipe up to 100 psi. They are also easy to connect without special tools. The pipe is simply pushed into the connector and automatically locked by a barbed ring and sealed with an internal O ring. If they are approved for inside walls that was good enough for me.

I found a system at my local hardware store called PEX. It is used to plumb houses and buildings instead of using expensive copper pipe. The connectors are guaranteed not to leak or blow out of the pipe up to 100 psi. They are also easy to connect without special tools. The pipe is simply pushed into the connector and automatically locked by a barbed ring and sealed with an internal O ring. If they are approved for inside walls that was good enough for me.

I bought two 100’ foot coils of ½” inch pipe, one red for hot water the other blue for cold. I pulled this new piping throughout the whole boat by taping it securely to the old pipes, and hauling it through. Except that I also re-routed much of it more directly, so I could inspect it easily and get at any suspect connections. I also bought numerous connectors that I thought I might need, elbows, tees, splices, etc. It took four days to completely re-pipe the whole water system, and I was quite pleased with the finished installation that looks very professional, with twin colors side by side and nice new connectors. Now I had to decide how to somehow automatically close off the water supply, in the event of another failure, however remote.

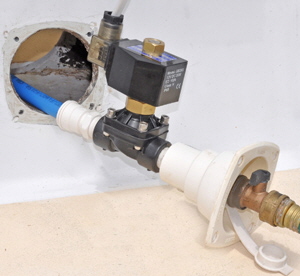

I found an electric shut-off valve on the web. It was a 12-volt solenoid valve that is normally open by default, but closes when voltage is applied. I connected it to the water pipe directly after the inlet connection, then wired it to the boat's bilge float. When the float is activated by rising water it activates the valve, that closes and stops any more shore water entering, simple.

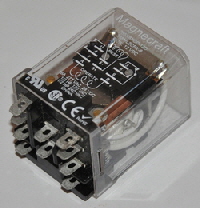

At least I thought it would be that simple, but on testing it I soon realized that when the bilge is emptied and the float sinks it switches itself off and the power to the solenoid switched off as well, and the solenoid reopens, allowing pressurized water to flow in again, and the cycle repeats continuously. After consultation with an electrician friend I bought what is called a “latching relay.” This is a relay that, when the primary activating current switches off from the bilge float switch, the relay stays on, maintaining power to the solenoid and keeping it shut. The relay opens only when an ‘unlatch’ current is applied. The latching relay is Part # 785XBXCD-12D from Zoro.com. This solved the problem and has worked flawlessly so far. But I still disconnect the pipe at the shore when I leave the boat… Later I incorporated a bell that rings when the system is activated, and I now have a high water bilge alarm. I also fitted a secondary shut-off valve on the end of the water pipe, so I can now physically also shut off the water at the boat as well as the shore. This is a double safety measure, just in case someone switched the shore faucet on.

At least I thought it would be that simple, but on testing it I soon realized that when the bilge is emptied and the float sinks it switches itself off and the power to the solenoid switched off as well, and the solenoid reopens, allowing pressurized water to flow in again, and the cycle repeats continuously. After consultation with an electrician friend I bought what is called a “latching relay.” This is a relay that, when the primary activating current switches off from the bilge float switch, the relay stays on, maintaining power to the solenoid and keeping it shut. The relay opens only when an ‘unlatch’ current is applied. The latching relay is Part # 785XBXCD-12D from Zoro.com. This solved the problem and has worked flawlessly so far. But I still disconnect the pipe at the shore when I leave the boat… Later I incorporated a bell that rings when the system is activated, and I now have a high water bilge alarm. I also fitted a secondary shut-off valve on the end of the water pipe, so I can now physically also shut off the water at the boat as well as the shore. This is a double safety measure, just in case someone switched the shore faucet on.

Just for interest I made a rough estimate of how much water had flooded into Britannia’s hull. It was quite a complicated geometric volume calculation and measurement, because the bilge is not uniform in shape all along its length, but it was fairly accurate, and certainly an eye-opener. I estimated that some 700 gallons had flooded in. One gallon of water weighs 8.34lbs, so the total weight of water was just under three tons! No wonder the old gal’ went down so far on her marks.

Feeling quite satisfied with myself after installing my new pipes and fail-safe system, I decided to find out how many boats were connected to the shore water in the marina. Out of a total of 20 boats that I could see with shore water hoses connected, I spoke to the owners of twelve. I asked if they had any safety system in case of an internal pipe failure while they were away from their boat. Amazingly absolutely none did, and had not even thought about it! They all said they relied entirely upon remembering to switch the water off when they left. That’s what I thought…I told them, and I hope they read this story.

A cautionary tale.