There can be few instruments more important on a boat than that which shows the amount of fresh water in the tanks. If there is one thing you need to know on a cruising boat, especially if it doesn't have a water-maker, it is an accurate indication of how much drinking water you have.

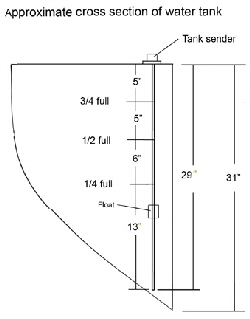

Britannia has two stainless steel water tanks amidships, one on each side. The shape follows the curve of the hull and is therefore somewhat triangular in cross section, tapering to a point at the base. This makes accurate calibration of any type of measuring system difficult because when the water is half way down the vertical side of the tank, the actual capacity is only about 1/3rd full.

The original system was, pneumatic, i.e. air operated, that was supposed to read the air pressure differential as the water level in the tanks varied but it alwasy leaked and did not read correctly.

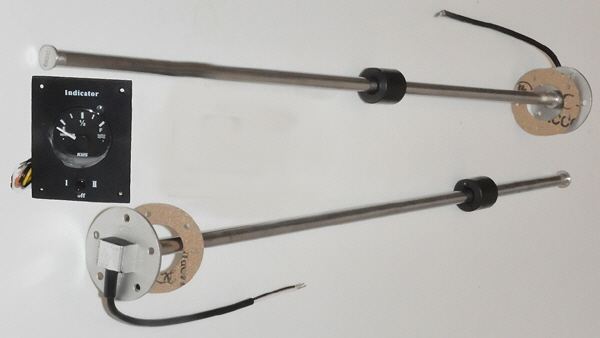

An electrically operated device was fitted that also uses a vertical tube in the tanks, but instead of working on air pressure it has a float that travels up and down the tube, activating electrical signals inside the stainless steel tube that are then read by the gage. It is made by Wema/Kus USA. Fort Lauderdale, Florida. www.wemausa.com/sensors/level-FuelWater

An electrically operated device was fitted that also uses a vertical tube in the tanks, but instead of working on air pressure it has a float that travels up and down the tube, activating electrical signals inside the stainless steel tube that are then read by the gage. It is made by Wema/Kus USA. Fort Lauderdale, Florida. www.wemausa.com/sensors/level-FuelWater

The system was calibrated to the exact tank shape to ensure the gage read the correct capacity of water in the tank throughout the whole range. The actual capacity of each tank is 168 US gallons each side, 268 Imperial UK gallons or 1272 liters. The duel gage mounted on a single panel with a switch shows either port or starboard tank. In the middle the switch is off and no electric current is being used. The gage also lights up when reading a tank and there is a choice between red and yellow illumination.

The gage regesters accurately throughout the whole range and It is now a great relief to have a reliable record of water capacity for each tank.