Squaresails have been used on sailing vessels for centuries and there is little argument between “square riggers’” that when the wind is dead astern, or a few points either side, a squares’l is still a very efficient way to propel a boat of any size, even today.

Anyone with triangular Bermudan sails knows how tricky it can be to keep them filled and hold a steady course when running before the wind, especially when a big sea is rolling up astern. It is often necessary to set preventer poles and an assortment of lines to hold the sails out, and certainly for a spinnaker. Even with these, the helmsman will still need to keep a keen eye on the wind and the course to prevent the sails collapsing then re-filling with a loud ‘crack’, imposing great strain on the sail and rigging. Another concern with most of these head sail configurations especially twin headsails, is that they cannot easily be reefed and as the wind picks up hands have to go forward to deal with the situation. With a squaresail correctly braced there is absolutely none of this and the boat becomes very stable. Yet the course can vary widely, by as much as 30 to 40 degrees either side. There is no concern about gybing or broaching and the helmsman or autopilot will have little difficulty in keeping a steady downwind run.

However, there is a significant almost insurmountable drawback to having a great flat sheet of canvas hanked on a yard high up a mast and billowing forth. That is, furling and unfurling the sail, not to mention reefing it. This single issue precludes the use of squaresails on all but vessels with large crews, like sail training ships with lots of young people able to scale the ratlines and edge out along a flimsy foot ropes to secure or release the canvas from the yard.

But what if the sail could be furled and reefed from the safety of the deck, or better still the cockpit, without a single person having to go aloft?

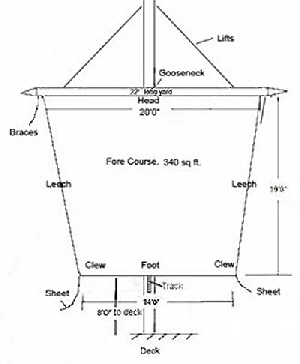

Britannia has a beautiful squaresail on her foremast. It is called the Fore Course, being the lowest athwart sail on a ships mast, in her case the foremast. It has proved to be flawless for sailing down wind, and all furling and unfurling is done from the safety of the cockpit. The sail can be rolled up or down, or reefed part way according to the wind strength. When completely furled the yard presents little windage and the sail is protected from the elements inside the tubular spar and never gets wet even in the heaviest deluge.

Britannia has a beautiful squaresail on her foremast. It is called the Fore Course, being the lowest athwart sail on a ships mast, in her case the foremast. It has proved to be flawless for sailing down wind, and all furling and unfurling is done from the safety of the cockpit. The sail can be rolled up or down, or reefed part way according to the wind strength. When completely furled the yard presents little windage and the sail is protected from the elements inside the tubular spar and never gets wet even in the heaviest deluge.

The goose neck attaches the yard to the mast. It is a very strong and secure connection from the center of the yard. Yet it also is easily detachable in case the sail jammed or other emergency. It pivots from side to side to brace the yard left or right according to the wind. It also rotates to permit the yard to cant (tilt), when docking in confined marinas.

The goose neck attaches the yard to the mast. It is a very strong and secure connection from the center of the yard. Yet it also is easily detachable in case the sail jammed or other emergency. It pivots from side to side to brace the yard left or right according to the wind. It also rotates to permit the yard to cant (tilt), when docking in confined marinas.

All the foremast rigging sizes, including the two fore-stays and triatic stay are 3/8 inche, and there are two running backstays instead of one.

When running before the wind Britannia does not heel or roll like a Bermudian rig. The motion is more like a catamaran and very steady. Knowing the sail can be progressively reefed to just a few feet of canvas will be a great reassurance as the wind pipes up.

The furling line in the cockpit is a continuous rope loop. This goes three times round the winch and back to the clutch which considerably reduces the line length on a conventional rig. To make winding the furling winch easiert an electric winch handle effortlessly spins winches twice as fast as by hand, and winds the squaresail up in minutes. This labor-saving device can also be used on all the other winches.