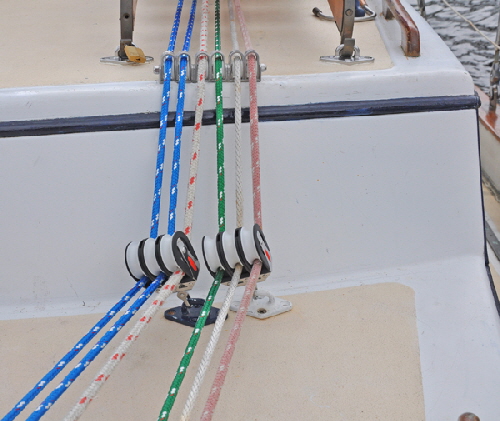

Even in our younger days my wife and I tried to make things as easy as possible on our cruising boats and this is even more important as we grow older. To make the sails easier to handle on Britannia I changed all five to roller furling. I also wanted to route all the control lines, furling lines, sheets, and out-hauls to our center cockpit so we wouldn't have to go forward to furl or reef in inclement weather or rough seas. This resulted in twelve lines passing along the deck(s) into the cockpit in two rows of six. This does not include the five sheets that route to cockpit winches in the normal way.

Even in our younger days my wife and I tried to make things as easy as possible on our cruising boats and this is even more important as we grow older. To make the sails easier to handle on Britannia I changed all five to roller furling. I also wanted to route all the control lines, furling lines, sheets, and out-hauls to our center cockpit so we wouldn't have to go forward to furl or reef in inclement weather or rough seas. This resulted in twelve lines passing along the deck(s) into the cockpit in two rows of six. This does not include the five sheets that route to cockpit winches in the normal way.

This was not difficult to plan, and the fairleads, clutches, winches, and pinrails would not be difficult to make and install, but a slight problem did remain. Britannia has three deck levels: the lower fore deck, the forward coach roof deck and the saloon coach roof deck. To reach the cockpit lines had to be brought up from one level to the next and the next. The jib and fore staysail furling lines and the fore staysail out-haul were the longest. These had to pass down to the fore deck then over both coach roof levels to the cockpit.

Bringing lines down from aloft and along a deck is easy, using blocks anchored to the deck and through line organizers. But routing lines upward and over the edge of a coach roof requires what are commonly called “over the top blocks.”

Bringing lines down from aloft and along a deck is easy, using blocks anchored to the deck and through line organizers. But routing lines upward and over the edge of a coach roof requires what are commonly called “over the top blocks.”

By any standard we had a lot of lines, but I knew how I would handle them once they arrived up to the cockpit. They would come through the front of the Bimini and through two banks of six rope clutches on either side of the companionway where it would be easy to reach and operate the clutches. Ropes would then feed to two Lewmar self-tailing winches then be coiled round a row of belaying pins to prevent tangles. They would be our port and starboard “rope decks.”

Over the top blocks are available from a few suppliers like Garhauer and West Marine for about $55 for a single line sheave and $85 for a double. Nobody seems to make more than a double sheave combination and if you have twelve lines that works out to be a very expensive exercise. In any case, all the over the top blocks I could find used large sheaves with diameters of 2” inches or more. This results in the lines running about 3” inches clear of the deck and the very serious possibility of someone, i.e. me, tripping over them. I therefore wanted my lines as close to the deck as possible, the same as line organizers, to minimize that eventuality. My first thought was to use bulls-eye fairleads with stainless steel inserts. These are really intended to lead ropes in straight lines not at different angles, and are often used to route roller furling lines along stanchion rails. Still, I decided to give them a try and screwed six to my deck, but the nearly 90 degree up and over angle resulted in a lot of friction and a good chance of rapid chafe, especially for those lines that must rise up two deck levels.

Over the top blocks are available from a few suppliers like Garhauer and West Marine for about $55 for a single line sheave and $85 for a double. Nobody seems to make more than a double sheave combination and if you have twelve lines that works out to be a very expensive exercise. In any case, all the over the top blocks I could find used large sheaves with diameters of 2” inches or more. This results in the lines running about 3” inches clear of the deck and the very serious possibility of someone, i.e. me, tripping over them. I therefore wanted my lines as close to the deck as possible, the same as line organizers, to minimize that eventuality. My first thought was to use bulls-eye fairleads with stainless steel inserts. These are really intended to lead ropes in straight lines not at different angles, and are often used to route roller furling lines along stanchion rails. Still, I decided to give them a try and screwed six to my deck, but the nearly 90 degree up and over angle resulted in a lot of friction and a good chance of rapid chafe, especially for those lines that must rise up two deck levels.

Then I discovered that Ronstan made nylon sheaves only 1 3/32” inches diameter, yet wide enough to handle up to a ½” inch line. As three of my lines are ½” inch and the rest are 3/8” inch, this size sheave would work with all of them. They are only $3.95 each, part number RF128. I decided to try to make my own over the top blocks using these sheaves, and for anyone who has the same problem, here is how I made the.

TOOLS

I shaped my over the top blocks by hand, using tools that most boat owners probably have. It's not rocket science, but some of the operations do require careful measurement and accurate drilling.

I shaped my over the top blocks by hand, using tools that most boat owners probably have. It's not rocket science, but some of the operations do require careful measurement and accurate drilling.

The tools I used were a caliper gauge for accurate measuring, a sharp scribe for marking, a strong vise with aluminum soft jaws, three vise grips and a 5/8” inch diameter mandrel to bend the strips round to form the arches. In my sockets box I found a socket that was exactly 5/8” inch diameter, but any 5/8” inch round stock would work. A bench-press is better than trying to drill holes accurately by hand. The more precise the marking and drilling the better chance of making a smooth running sheave. It would therefore be a good idea to invest in a new sharp 1/4” inch drill bit, preferably the type with a pilot point that are easier to center by eye and drill an almost burr free exit hole. A countersink bit is another important tool for this job. After drilling or sawing, all raw edges should be cleaned with a deburring tool or a larger drill and file.

I would have preferred to make the blocks of stainless steel, but cutting and accurately bending and drilling even 1/8” inch stainless was beyond the capability of my equipment, so I choose aluminum. Aluminum can easily be hand sawn with a 24 tooth per inch hacksaw, but I also used a miter saw with a 10” inch diameter 60 tooth carbide-tipped blade, that cuts through aluminum like butter with a very straight clean cut. I made the bottom channels from a 12” inch length of 1/8” inch aluminum channel, 2” inches wide with 1” inch sides. I made the rope retaining arches from a 48” inch length of ½” inch x 1/8” inch aluminum strip. This was all available from my local hardware store for $15.

I needed to make one row of six sheaves, a row of three, one of two and a single, but most boats won't need that many and would therefore require less material.

MAKING THE BOTTOM CHANNELS

I first cut the channel into 1” inch wide pieces to form the base for a two sheave block, and I needed five of these.

The next drilling operation is critical and much easier and more accurate with a drill press. Both legs of the channel need to be accurately marked 3/4” inch from the bottom outside of the leg and in the center. I drilled a 1/4” inch hole at these marks from both sides of the legs. This hole position allows the sheaves to rotate clear of the bottom of the channel by 1/16” inch and the lines run out the top of the sheaves at the very lowest point about 1” inch off the deck.

Next I drilled and countersunk two 1/4” inch holes in the bottom of the channel 5/8” inch from inside the channel and in the center. This was to locate the attachment screws beneath the sheaves. As a final finish to the channels I rounded the square sharp corners of the legs with a flat file.

ROPE RETAINING ARCHES

To form the arches I cut the ½” inch aluminum strip into 5” inch lengths, so I could more easily bend each around my socket mandrel. I clamped the socket hard in the vise then marked the center of the strips and clamped one to the socket in the center with vise grips. This is to ensure that the aluminum strip will fold evenly round the mandrel in a perfect half circle, otherwise it would bow upward and not form correctly. I also cut some lengths of spare strip to put between the vice grip jaws both to prevent them cutting into the aluminum and to keep the legs of the arches straight.

|

I then carefully pulled both legs around the mandrel. It was quite easy with the vice grips to extend the leverage, but I could only bend so far before the vice grips come together, so I then just squeezed the two sides further with just one vice grip until they were parallel to each other in a perfect arch. Then I sawed the legs of the arch off square 1 5/8” inches from the top of the arch and using a round file and sandpaper I rounded the top inside edges a little to prevent the rope chafing as it passes through. A Dremel with a round sanding drum would be good for this purpose. Each arch is now 7/8” inch wide, so two will be a perfect snug fit inside the channel that measures 1 3/4” inches inside the legs.

DRILLING THE ARCHES

With both arches centered in the channel I clamped the assembly in the vice and with an electric drill, carefully and dead level, drilled either side of the arches through the hole in the channel leg. I then reversed the arches and making sure they were centered in exactly the same position I clamped them in the vise and drilled through the other side. Do not be tempted to try to drill straight through both arches, it is very unlikely you will be level using a hand drill. At this point it is possible to push a 2½” inch long 1/4” inch bolt straight through the channel and both arches, thus pinning them together. If your measuring or drilling has not been quite accurate enough to make its possible to push a bolt through, then just ream the holes level by carefully running a 1/4” inch drill through. I discovered some unevenness when assembling my row of three channels to make the six-sheave block, but I ran a 1/4” inch drill through the whole lot and they work perfectly when bolted together.

SHEAVES AND BUSHINGS

The Ronston nylon sheaves have a 5/16” inch center hole with no ball or roller bearings. I therefore bought some small 5/16” inch bronze bushings from my local Hardware store for only $2.35 each. These fitted perfectly inside the sheaves and reduced the hole to 1/4” inch. Unfortunately, they were only available in 3/4” inch lengths, so I had to carefully saw and file 1/8” inch off one end to make them 5/8” inch long to fit snuggly inside the arches. As a line passes through, the sheaves rotate on the bushings and the bushings rotate on the bolt giving an almost friction free roller bearing surface for the rope. If the sheaves don't rotate completely freely something is wrong. Perhaps the bushing was distorted in sawing it shorter, or it needs to be deburred on the inside and maybe also the outside.

ASSEMBLY

The photo of the two sheave assembly shows it with no lines running through. To fix the channels to my fiberglass deck I used 3/4” inch long #12 countersunk self-tapping screws that finished flush with the bottom of the channel in the countersunk hole. I screwed these directly into the deck and bedded them with 3M 4000 sealant. It did not seem necessary to bolt these blocks straight through a deck as you would for a deck-eye because when the ropes are under load they press the assembly down to the deck, instead of pulling it upwards. It is necessary to fix the channel to the deck before assembling the sheaves then assemble the rest in situ.

The photo of the two sheave assembly shows it with no lines running through. To fix the channels to my fiberglass deck I used 3/4” inch long #12 countersunk self-tapping screws that finished flush with the bottom of the channel in the countersunk hole. I screwed these directly into the deck and bedded them with 3M 4000 sealant. It did not seem necessary to bolt these blocks straight through a deck as you would for a deck-eye because when the ropes are under load they press the assembly down to the deck, instead of pulling it upwards. It is necessary to fix the channel to the deck before assembling the sheaves then assemble the rest in situ.

Just before this final assembly I used a dab of winch grease on the bolt and bushings, but not on the bushing to nylon sheave surface. The sheaves and bushings are positioned inside their arches and the arches are pushed into the channel. Then the bolt is passed through the whole lot and secured with a thin washer and nylock nut. I found it best not to tighten the bolt too much allowing some play in the bearing surfaces so everything rolls freely.

The photo of six sheaves shows how I joined three two block assemblies to make a neat row of six. It was just a matter of using a 6” inch bolt through all three assemblies. To mount a multi-sheave combination it is best to bolt them all together without the sheaves or arches, then position them where you want them on the deck, mark the attachment hole centers then

The photo of six sheaves shows how I joined three two block assemblies to make a neat row of six. It was just a matter of using a 6” inch bolt through all three assemblies. To mount a multi-sheave combination it is best to bolt them all together without the sheaves or arches, then position them where you want them on the deck, mark the attachment hole centers then  drill the holes for the fasteners.

drill the holes for the fasteners.

To make the three sheave block I cut one leg off a channel, then made a corresponding half channel to butt against it. A 3½ ”inch bolt goes straight through all three sheaves locking them together, then a fastener beneath each secures them to the deck.

The single sheave leads the jib furling line down to the fore-deck, so it can be routed up and over the forward coachroof and the saloon coachroof. This block was also made using half a channel, but it has a different shape so I could screw it to the toe rail. I secured a small half channel with one of the screws to fix it to the toerail and a 1 1/4” inch bolt fastens the assembly together.

The single sheave leads the jib furling line down to the fore-deck, so it can be routed up and over the forward coachroof and the saloon coachroof. This block was also made using half a channel, but it has a different shape so I could screw it to the toe rail. I secured a small half channel with one of the screws to fix it to the toerail and a 1 1/4” inch bolt fastens the assembly together.

These combinations demonstrate the versatility of this method of making over the top blocks and there's no reason why longer combinations could not be bolted together as needed. Finally, if you want to make these blocks look really professional, polish all the individual pieces on a bench grinder with a large polishing wheel and graphite applicator. The aluminum will shine like new chrome.

My over the top blocks work marvelously and the lines look very neat running close to the deck with little chance of anybody tripping over them.

The total cost in materials was about $120 for twelve blocks, or $10 for each. This is quite a savings compared to buying commercial units for about $500. This does not count my labor of course, but on boats that's supposed to be fun.

A method to overcome a common rope problem on different deck levels