It was with considerable trepidation and anxiety that my wife and I left Britannia, our 50’ foot schooner, all alone to face a category four hurricane in a marina at Titusville, on the east coast of Florida near Cape Canaveral, USA.

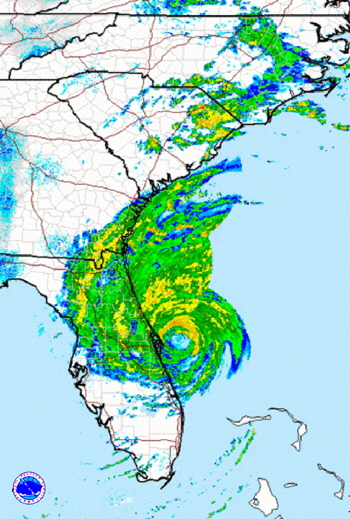

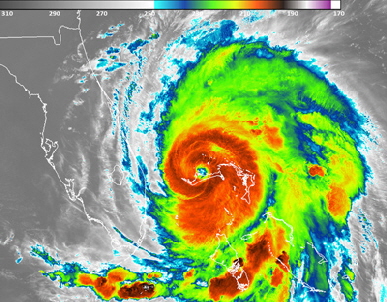

The monster storm heading our way had been named Matthew and had already wreaked havoc and caused many deaths in Haiti and the Bahama Islands. It was now barreling north with a projected landfall in the USA, exactly at Cape Canaveral. From past experience we knew we were in for a severe hammering, because even if Mathew only passed nearby the beast was so large, with very strong winds extending some 40 miles from the eye, it would still impact us. Wind speeds were forecast at around 100 to 150 miles per hour along the coast, with the possibility of even more devastating gusts. Another phenomenon associated with hurricanes are local tornadoes that are sometimes even more severe than the actual storm they spin off. They are usually short lived, but can cut a clear swath through a neighborhood, leaving some houses standing and next door flattened.

The monster storm heading our way had been named Matthew and had already wreaked havoc and caused many deaths in Haiti and the Bahama Islands. It was now barreling north with a projected landfall in the USA, exactly at Cape Canaveral. From past experience we knew we were in for a severe hammering, because even if Mathew only passed nearby the beast was so large, with very strong winds extending some 40 miles from the eye, it would still impact us. Wind speeds were forecast at around 100 to 150 miles per hour along the coast, with the possibility of even more devastating gusts. Another phenomenon associated with hurricanes are local tornadoes that are sometimes even more severe than the actual storm they spin off. They are usually short lived, but can cut a clear swath through a neighborhood, leaving some houses standing and next door flattened.

With the approach of hurricane strength winds, a very serious consideration for boat owners is whether to lift the boat onto the hard, or leave it in the water. Different parameters apply to each storm and the boats location even in the same marina. For example, it is not just a question of whether your lines will hold in hurricane force winds, but whether the actual marina dock will hold! This is not an idle concern either, because many marinas have been completely wiped out by hurricanes, with boats and bits of the marina tossed ashore in piles, or sunk under the intense wind and rain and monster storm surges

Marinas that have travel lifts are usually in great demand when a hurricane is known to be on the way. Boats are lifted, then chocked on stands and in some marinas fastened down with truck type webbing straps, tightened to rings in concrete slabs. The marina Britannia was in is considered a “hurricane hole” because it is well protected inside the US Intracoastal Waterway system (ICW) by a massive lock at the Canaveral Sea Port, and by the outer banks. Past experience had shown us that we would be unlikely to experience severe storm surge, so I decided to put my trust in my own heavy lines that would offer some “give,” rather than the marina's rigid support props. Britannia was moored bow to the dock, between stout pilings, (I hoped), forward, amidships and aft, on either side.

Marinas that have travel lifts are usually in great demand when a hurricane is known to be on the way. Boats are lifted, then chocked on stands and in some marinas fastened down with truck type webbing straps, tightened to rings in concrete slabs. The marina Britannia was in is considered a “hurricane hole” because it is well protected inside the US Intracoastal Waterway system (ICW) by a massive lock at the Canaveral Sea Port, and by the outer banks. Past experience had shown us that we would be unlikely to experience severe storm surge, so I decided to put my trust in my own heavy lines that would offer some “give,” rather than the marina's rigid support props. Britannia was moored bow to the dock, between stout pilings, (I hoped), forward, amidships and aft, on either side.

Our regular lines are 1” inch diameter and under normal conditions would support the whole 22 tons of the boat, but what was irrevocably lurching towards us was very very different from normal conditions. I therefore doubled the bow and stern lines, along with the fore and aft springs on both sides. I also set ‘midship lines to the pilings either side. There were a total of fourteen lines.

Our regular lines are 1” inch diameter and under normal conditions would support the whole 22 tons of the boat, but what was irrevocably lurching towards us was very very different from normal conditions. I therefore doubled the bow and stern lines, along with the fore and aft springs on both sides. I also set ‘midship lines to the pilings either side. There were a total of fourteen lines.

To reduce windage to an absolute minimum I removed the three roller furling sails, the jib, fore staysail, and ‘tweenmast staysail. The mainsail was in-mast roller furled, so it was safe enough provided the rigging held? I just secured the exposed mainsail clew to stop it flapping about. I lowered the 22’ foot long yard, (Britannia is a brigantine schooner), with its roller-furled squaresail inside and lashed it on deck. I also lowered the three booms to the deck and tied them off to stop them ranging around. The awning was removed along with the Bimini. All the cockpit cushions, hatch covers and everything else on deck were all stowed below. Inside we secured everything that could possibly move because we knew the boat would heel at an unnatural angle in the fierce winds. Heeling would actually be an advantage because the boat would lean with the wind, instead of being rigidly fastened like on land. I also closed all eleven sea cocks, except the cockpit drains. Finally, I took photographs of all our preparation just in case I needed them for an insurance claim afterwards.

To reduce windage to an absolute minimum I removed the three roller furling sails, the jib, fore staysail, and ‘tweenmast staysail. The mainsail was in-mast roller furled, so it was safe enough provided the rigging held? I just secured the exposed mainsail clew to stop it flapping about. I lowered the 22’ foot long yard, (Britannia is a brigantine schooner), with its roller-furled squaresail inside and lashed it on deck. I also lowered the three booms to the deck and tied them off to stop them ranging around. The awning was removed along with the Bimini. All the cockpit cushions, hatch covers and everything else on deck were all stowed below. Inside we secured everything that could possibly move because we knew the boat would heel at an unnatural angle in the fierce winds. Heeling would actually be an advantage because the boat would lean with the wind, instead of being rigidly fastened like on land. I also closed all eleven sea cocks, except the cockpit drains. Finally, I took photographs of all our preparation just in case I needed them for an insurance claim afterwards.

After all this Britannia looked very forlorn, like a puppy who had been tied to a post while its owner went into a shop, “You're not leaving me here all alone are you?” but I had already made that decision. For several years I had put my heart and money into my boat and I loved her dearly, but I was not prepared to risk my life by staying aboard, then go down with the ship if she sank. Having previously experienced 100 mph winds I knew there is precious little anyone can do in the height of a storm. In such fierce wind and biting rain it is difficult to even crawl along a deck and impossible to adjust lines.

The wind had already started to pick up to a paltry 40 mph as we left her at 6 pm the night before the full force of Matthew was due to arrive the next day. “Hang on old gal,” I said, “We'll see you in a few days,” and I gave her a little pat on her bowsprit as we prepared to head west to our home in Orlando, hopefully further away from the approaching storm. The marina had practically emptied out except for a few stalwart liveaboards who had little option to ride it out on their boats, and try to protect their only home.

The authorities had recommended everyone who could do so should evacuate the low lying coastal areas and move inland. Our 80 mile drive back to Orlando was therefore nose-to-tail and very slow. All hotel accommodation had been taken and shelters had been set up in school gymnasiums and public halls. We arrived back at our house and began the process of moving everything that could possibly move outside into our garage. We also found our store of candles and batteries for when the power inevitably went out.

We switched the television on that was broadcasting continuous reports of Mathew’s advance, then we waited. We watched the monster as it edged ever closer up the eastern coast of Florida. Thankfully the eye was projected to remain about 30 miles off shore, but even 110 miles away we experienced very strong winds and horizontal biting rain howling from the north east.

We switched the television on that was broadcasting continuous reports of Mathew’s advance, then we waited. We watched the monster as it edged ever closer up the eastern coast of Florida. Thankfully the eye was projected to remain about 30 miles off shore, but even 110 miles away we experienced very strong winds and horizontal biting rain howling from the north east.

During a very blustery night we heard many trees crash down on our street and our house lost a lot of roof tiles, but no other structural damage. One very big pine tree was blown over at the back of the house, luckily missing the garage Other people were not so lucky and had to have complete roofs replaced. For a few days the street was impassable and looked like a hurricane had hit it, because it had!!.

Matthew rolled on up the coast heading for Jacksonville, thankfully missing a direct hit on Cape Canaveral. The storm eventually make landfall in Georgia, causing extensive inland flooding and beach erosion.

A few days later we were allowed back to the boat. The yard was eerily quiet and a complete shambles with debris strewn everywhere. A large Moody 45 had been blown off its stands on the hard and taken two other boats with it, snapping masts and booms like matchwood. Sails, awnings and covers that had not been removed were shredded.

As we walked down our dock Britannia seemed to be sitting exactly as we had left her. But when you have worked on a boat as extensively as I have over the years, it doesn't take but a minute to spot irregularities. The first thing I noticed was the pulpit grating, smashed on the port side and the dolphin striker was missing, causing the bobstay to go slack. As I edged down the side to the cockpit I noticed a long length of the port toe-rail had broken, and as I walked round the deck the starboard side was also broken for a six foot length.

As we walked down our dock Britannia seemed to be sitting exactly as we had left her. But when you have worked on a boat as extensively as I have over the years, it doesn't take but a minute to spot irregularities. The first thing I noticed was the pulpit grating, smashed on the port side and the dolphin striker was missing, causing the bobstay to go slack. As I edged down the side to the cockpit I noticed a long length of the port toe-rail had broken, and as I walked round the deck the starboard side was also broken for a six foot length.

This damage was difficult to fathom because the boat was sitting exactly as we had left her, clear of all the pilings and with fenders undamaged and in the correct position. later I learned that as the wind had backed and started to come from the west, it had pushed water out of the marina entrance and lowered the level by an astonishing three feet. This had caused the mooring lines to go slack and caused Britannia to range violently from side to side and forward and back smashing into the two side pilings and on the dock at the bow. Marks on the marina decking planks confirmed this and I shudder to think what she went through for about six hours, as Matthew's winds battered her.

It was upsetting to see the damage, but being a skilled carpenter I knew there was nothing I couldn't fix myself. We had evidently done a good job inside because everything was as we left it, thankfully.

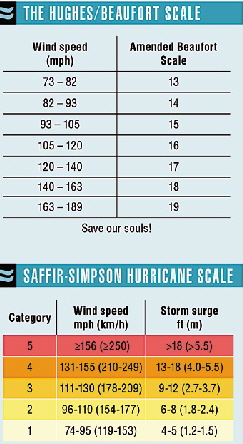

I felt vindicated with my decision to leave the boat when I heard from one experienced cruiser who had weathered the storm. He had found it impossible to alter his own lines during the initial 3’ feet water level rise that flooded the docks. At the height of the storm he recorded a wind speed at 105 knots, (120 mph) and micro-gusts in excess of that. This is force 17 on the Hughes/Beaufort scale, see below.

Of course, ours was far from the only boat to suffer damage. A work boat sank in the next dock to us, flooded and with a defective bilge pump. Out of seven boats anchored unattended in the Intracoastal Waterway just outside the marina, five dragged and sank on the rocky shore. A 45’ foot ketch broke free from the City Municipal mooring field, smashed into the nearby bridge and sank. A boat in the City Marina also sank, its spade rudder being damaged and allowing water to enter through the rudder post sealing gland.

An elderly couple who lived on an old house-boat in the marine had moved many of their possessions into a rental storage building, because they worried that their floating home might actually sink. It was still in one piece after the storm passed, but the roof of the storage building had been torn completely off and the incessant torrential rain had saturated all their possessions. In their rush to leave they had omitted to buy insurance at the storage unit and a collection was contributed to by all the boat owners, to go some way towards helping the unfortunate couple.

WHAT IS A HURRICANE?

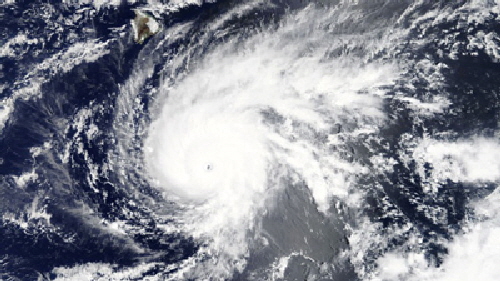

So what causes these horrendous monsters, that can easily be 600 miles wide and render so much devastation and death on land and sea? In simple terms they start as areas of low atmospheric pressure over warm waters, around which wind rotates in a counter clockwise spiral, (clockwise in the southern hemisphere) just like any cyclonic low, but in a much tighter spiral. In the north Atlantic they usually begin innocently enough, with warm winds blowing off the Sahara Desert and over the sea around latitude 14-16 degrees north, near the Cape Verde Islands. Although hurricanes can start anywhere where the right mixture of warm air and warm water is present. The wind begins to rotate like in a tunnel and form a central core, called an eye. This in turn starts to draw moist sea air upwards into the core that further tightens the rotation. This cycle then becomes self-feeding and expands outwards, while the whole thing also moves forward. It is a bit like a whipping top that spins forcefully along, remaining upright by its centrifugal rotation. The difference between a spinning top and a hurricane however is the top slows down and falls over, but hurricanes speed up and become more powerful!

So what causes these horrendous monsters, that can easily be 600 miles wide and render so much devastation and death on land and sea? In simple terms they start as areas of low atmospheric pressure over warm waters, around which wind rotates in a counter clockwise spiral, (clockwise in the southern hemisphere) just like any cyclonic low, but in a much tighter spiral. In the north Atlantic they usually begin innocently enough, with warm winds blowing off the Sahara Desert and over the sea around latitude 14-16 degrees north, near the Cape Verde Islands. Although hurricanes can start anywhere where the right mixture of warm air and warm water is present. The wind begins to rotate like in a tunnel and form a central core, called an eye. This in turn starts to draw moist sea air upwards into the core that further tightens the rotation. This cycle then becomes self-feeding and expands outwards, while the whole thing also moves forward. It is a bit like a whipping top that spins forcefully along, remaining upright by its centrifugal rotation. The difference between a spinning top and a hurricane however is the top slows down and falls over, but hurricanes speed up and become more powerful!

The intensity and power of a hurricane is labeled through five categories on what is called the Saffir-simpson scale a bit like the Beaufort scale with which all mariners are familiar. The big difference and it really is a BIG DIFFERENCE, is that a category 1 hurricane STARTS AT FORCE 12 where the Beaufort scale tops off! Herbert Saffir and Robert Simpson devised the scale in 1970, with category 1 wind intensity starting at 74 mph in which it is already practically impossible to stand up, right through to category five, that starts at 156 mph!!

The intensity and power of a hurricane is labeled through five categories on what is called the Saffir-simpson scale a bit like the Beaufort scale with which all mariners are familiar. The big difference and it really is a BIG DIFFERENCE, is that a category 1 hurricane STARTS AT FORCE 12 where the Beaufort scale tops off! Herbert Saffir and Robert Simpson devised the scale in 1970, with category 1 wind intensity starting at 74 mph in which it is already practically impossible to stand up, right through to category five, that starts at 156 mph!!

The northern hemisphere hurricane season officially starts on June 1st and ends on November 30th, but hurricanes have started before and after these dates. The greater number come between September and October, As soon as a storm attains an internal wind speed of 39 mph it is labeled a tropical storm and given a name, starting alphabetically with the first of the season. A tropical storm upgrades to hurricane classification when it reaches 74 mph, or force 12 Beaufort.

In order to give some idea of the rising severity of the hurricane scale I have interpolated the numbers on a chart at roughly the same gradient as the Beaufort scale. If you have ever been at sea in weather at the top end of Admiral Beaufort's scale, you certainly wouldn't want to be at sea in weather on any of the Hughes/Beaufort scale, that starts at force 13 right through to force “God help us!

The principal American hurricane tracking agency is the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, (NOAA) with its National Hurricane Center in Miami, Florida. www.noaa.gov They track the start of weather patterns by satellite and specially equipped planes that fly directly through these strong winds, adding a new dimension to “a little turbulence”. NOAA is amazingly accurate in forecasting a hurricane's projected path and intensity. They use different highly sophisticated computer models to interpolate the projected path that naturally can change as the storm progresses though different water temperatures and atmospheric conditions. Another superb, but rather innocuously named meteorological site is Mike's Weather Page, that has an amazing array of charts and information about all the worlds weather, not just hurricanes. http://spaghettimodels.com/ Another is http://Windy.com

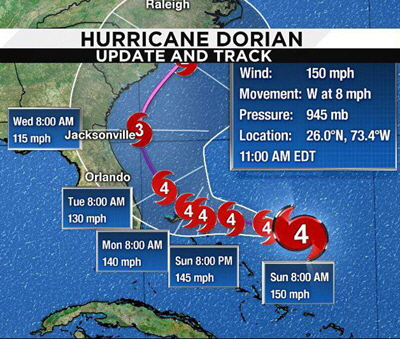

The speed that hurricanes travel over land and water has a profound effect upon the destruction they cause. In August/September 2019 hurricane Dorian came up “hurricane alley,” the well trodden route through the Caribbean islands. It shuffled along at a normal speed of around 12/15 knots and whilst it caused extensive damage to every country it passed, it did pass over some islands in a matter of hours. That is, until it arrived at the Bahama island of Abacus as a gigantic category 4, that was the biggest storm ever recorded in the Bahamas, where it slowed to 2 mph. For nearly three days this horrendous behemoth flattened and flooded everything, and the embattled residents had to endure rain, wind and noise of hellish proportions with little protection, electricity or water. Their only consolation must have been that NOAA forecast Dorian would move on

The speed that hurricanes travel over land and water has a profound effect upon the destruction they cause. In August/September 2019 hurricane Dorian came up “hurricane alley,” the well trodden route through the Caribbean islands. It shuffled along at a normal speed of around 12/15 knots and whilst it caused extensive damage to every country it passed, it did pass over some islands in a matter of hours. That is, until it arrived at the Bahama island of Abacus as a gigantic category 4, that was the biggest storm ever recorded in the Bahamas, where it slowed to 2 mph. For nearly three days this horrendous behemoth flattened and flooded everything, and the embattled residents had to endure rain, wind and noise of hellish proportions with little protection, electricity or water. Their only consolation must have been that NOAA forecast Dorian would move on  within two days. A normal direct path from Abacus is across the Florida Straits into the USA and one of the heaviest congregation of boats and marinas in the world. At one point NOAA forecast that Dorian would pass straight over Orlando where we live, still as a category 4, but a day later they changed the projection saying the storm would make an almost 90° degree right turn, then travel North up the side of Florida but out to sea, basically following the Gulf Stream. This seemed incredulous to us, but turn it did and most of the property in this highly developed and very expensive coastline between Miami and Jacksonville was spared the brunt of the storm, including Britannia. Although hurricanes are very large circular storms the strongest winds are always on the right, (eastern), side of the rotation so even though we felt the effects of Dorian on the western side, it was much less than on the eastern side out to sea, where NOAA sea buoys recorded 30 foot high seas.

within two days. A normal direct path from Abacus is across the Florida Straits into the USA and one of the heaviest congregation of boats and marinas in the world. At one point NOAA forecast that Dorian would pass straight over Orlando where we live, still as a category 4, but a day later they changed the projection saying the storm would make an almost 90° degree right turn, then travel North up the side of Florida but out to sea, basically following the Gulf Stream. This seemed incredulous to us, but turn it did and most of the property in this highly developed and very expensive coastline between Miami and Jacksonville was spared the brunt of the storm, including Britannia. Although hurricanes are very large circular storms the strongest winds are always on the right, (eastern), side of the rotation so even though we felt the effects of Dorian on the western side, it was much less than on the eastern side out to sea, where NOAA sea buoys recorded 30 foot high seas.

WHAT IS IT LIKE AT SEA IN A HURRICANE.

My wife and I once delivered a 77’ foot Alden ketch from Bermuda to Florida in August, in the middle of the hurricane season. It is a westerly passage of approximately 950 miles, so naturally we checked with NOAA if there were any hurricanes, or even lesser tropical storms on the way up from the south. It was declared to be clear except that there was “intense weather activity” along our route, that was straight through the notorious Bermuda Triangle.

For three days we sailed with 15 to 20 knots from the south, a fabulous broad reach with all sails set. Then we started to see lightning activity ahead on the 70 mile radar. As we approached the first ominous big black mushroom cloud I was very glad I had dropped the large mainsail and reduced the mizzen and jib, Winds rapidly picked up to 60/70 knots (Force 11), and rain hammered us horizontally, but amazingly the sea was also flattened as we sailed for four hours, touching 15 knots at one point. Then we suddenly popped out the other side of the storm that ended abruptly, like a shower had just been switched off. However, there were others ahead...

In the middle of one of these I glanced up through the cockpit skylight and saw a perfect halo of fiery white light around the bright moon shining through a troubled sky. It was the phenomena called a lunar halo, caused by refraction of the moon's light through ice particles suspended within thin high altitude cirrus clouds. It looked like a horizontal rainbow surrounding the boat.

In the middle of one of these I glanced up through the cockpit skylight and saw a perfect halo of fiery white light around the bright moon shining through a troubled sky. It was the phenomena called a lunar halo, caused by refraction of the moon's light through ice particles suspended within thin high altitude cirrus clouds. It looked like a horizontal rainbow surrounding the boat.

Thanks to the long range radar we managed to dodge many of these storms by changing course and speed to pass behind them as they swept up from the south. The maximum winds we encountered in one of these was 75 mph, that is hurricane force 12 on the Beaufort scale but only the start of a baby category 1 on the Saffir-simpson range! In this wind it was very difficult to crawl along the deck, but even more incredulous to imagine it being twice as strong to even the start of a category five!

It was not difficult to understand how Spanish treasure ships, overloaded with booty and top heavy at the best of times could be completely engulfed and sunk in these storms, where seas could easily be as high as the mast. They plodded across the Gulf of Mexico and along the bottom of Florida, without the slightest inkling of what terror might be approaching from the south.

Thankfully category 4 and 5 hurricanes have rarely made landfall in the USA, but when they have they have left names to go down in history, especially in Florida. Hurricane Andrew in 1992 with 175 mph winds left 65 dead: Sandy in 2012 115 mph 233 deaths: Harvey in 2017 with 130 mph winds: Michael in 2018 with 28 deaths, and most recently Dorian in 2019, a category 5 with some 100 dead in the Bahamas alone.

The most deaths associated with any hurricane that struck the American mainland came from Katrina in 2005, when more than 1250 people perished, as it plowed into low lying New Orleans, breaching the levies and causing extensive flooding. Katrina actually originated in the Bahamas and made landfall as a category 3, with (only) 115 mph winds.

Some friends bought a big Ta Chiao CT54 ketch in the Cayman Islands in February 2012 and decided to sail it into the Northern Chesapeake Bay area to work on it for a year, where it would undoubtedly be “safe from hurricanes.” In mid October hurricane Sandy barreled its way up the eastern seaboard of the USA, completely missing Florida, and making devastating landfall on the New Jersey shore with 120 mph category 4 winds. It then passed right over the top of my friend's boat on which they were living and frightening the life out of them. They said it was as though mother nature was laughing at them, saying “That'll teach ‘ya.” Coincidentally my friends girlfriends name was also Sandy, so henceforth she is known as “Hurricane Sandy.”

Laura made landfall between Houston and New Orleans as a category 4 on 27th August 2020. This is a low-lying area with many small seaside towns. Sustained winds were in the order of 130/150 mph, that is difficult for anyone who has not experienced a hurricane to even comprehend. For sailors who have maybe experienced a mere gale 8 on the Beaufort scale, Laura's strength was the equivalent of force 17 on my Hughes/Beauford scale!! These winds will blow houses apart, overturn 18 wheeler trucks, and destroy bridges and power lines.

The sea surge accompanying these horrendous winds is also unimaginable and Laura's was recorded at 15’ feet above mean high water springs. This flooded up to 30 miles inland and accounted for many deaths from people who refused to evacuate. Boats have been found 10 miles inland in people's yards, which is one way to make a boat delivery? An irony is that Laura was originally projected to swing up the eastern side of Florida, but as it progressed up the Caribbean it shifted to the west then missed Florida entirely.

For every hurricane that sweeps up from the south towards Florida, then miraculously bypasses us we are always conscious that, “There but for the grace of God go I.”

.

An unnerving experience

This is a free article which I hope you enjoy.

If you have a project to do, or a repair please support this site by buying an article for only $10.

Thanks ROGER.

SURVIVING HURRICANE MATHEW