The two levels of vinyl-coated wire lifelines on Britannia were well past their prime. Sections of the vinyl coating had faded into a dull brown, with parts chafed and cracked, exposing the wire, and many of the chrome fittings had lost their luster. If I accidentally ran my hand along an exposed section it often resulted in blood. They simply had to be replaced not only for safety and to restore a smooth surface but also for the appearance. Lifelines are intended to stop someone falling overboard, so that is the primary consideration in any replacement. But this does raise another important question; how does a person who does fall overboard get back on board through or over the lifelines?

Another real emergency that might require lowering lifelines is to launch a heavy liferaft from the deck. Britannia has an eight-man ocean raft in a canister on chocks in the center of the deck that weighs over 140 lbs. The lifelines would definitely need to be released or cut to allow the container to be launched.

The permutations for confusion if someone actually does go overboard are considerable and hardly predictable. It is therefore only sensible to take as many precautions as possible to prevent it and make retrieval easier. It is to be hoped that under conditions where a man overboard might be likely everyone would be wearing lifejackets and tethers. That would make the chances of hoisting someone back aboard much easier if a line could be tied to the harness safety ring, but lowering the lifelines would make any rescue even easier.

Britannia’s lifelines were the old style with a locking ring over the release lever. When the wires were tight it was very difficult to pry the ring back over the latch by hand and pliers were necessary to squeeze the latch. A new type of pelican hook from CS Johnson Inc. has a pin like a snap-shackle that releases the hook even with the lines in maximum tension. CS Johnson also has a neat little adjustment tool that fits in the center small hole of a tubular turnbuckle and is much better than pliers. I decided to replace all the end fittings with CS Johnson’s beaufitul chrome fittings.

Britannia’s lifelines were the old style with a locking ring over the release lever. When the wires were tight it was very difficult to pry the ring back over the latch by hand and pliers were necessary to squeeze the latch. A new type of pelican hook from CS Johnson Inc. has a pin like a snap-shackle that releases the hook even with the lines in maximum tension. CS Johnson also has a neat little adjustment tool that fits in the center small hole of a tubular turnbuckle and is much better than pliers. I decided to replace all the end fittings with CS Johnson’s beaufitul chrome fittings.

If for any reason lines cannot be released, a final option would be to cut the wire, but this requires long handled wire cutters for 3/16” inch thick wire. But what if the lifelines were rope, that would be easy to cut, but would rope be strong enough?

ROPE: Dyneema rope is stronger, size-for-size than stainless wire. The possibility of substituting rope for lifelines therefore becomes a viable possibility. I found Miami Cordage Inc., a rope maker hidden in the industrial depths of Miami, Florida who most recreational boaters will not have heard of. The sell direct and their prices are considerably less than the regular retail outlets most boaters use. Their 1/4” inch single braided 12 strand Dyneema has an amazing tensile strength of 8,000 lbs. The advantages over wire are:

1. 1/4” inch Dyneema is much stronger than 3/16” inch wire. Dyneema 8000 lbs, wire 3700 lbs.

2. Dyneema is not subject to corrosion or affected by rain or seawater, and easily inspected for chafe.

3. Any section of a rope lifeline can easily be lowered between stanchions because the line slides through stanchions and bends

easily, wire does not.

4. If necessary, rope lifelines can be cut with a sharp knife. 3/16” inch wire needs a long-handled wire cutter.

5. Rope lifelines can be replaced without tools or fittings, even on a passage.

6. A spare 50’ foot length of 1/4” inch rope lifeline is much easier to store than a coil of the same length of wire.

7. Dyneema is very much lighter than wire rope. Britannia’s wire lines weighed 13 lbs. The same length of Dyneema rope weighed

only 2.4 lbs.  Before I decided on using rope I wanted to answer one important question: Different manufacturers specify their ropes with different poundages, so what would be the actual failing poundage of my particular Dyneema lifeline setup?

Before I decided on using rope I wanted to answer one important question: Different manufacturers specify their ropes with different poundages, so what would be the actual failing poundage of my particular Dyneema lifeline setup?

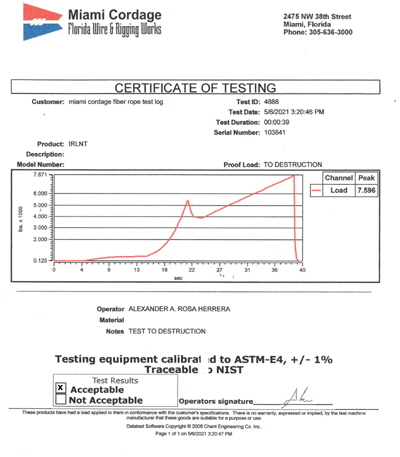

Miami Cordage have a 40’ foot long hydraulic rope testing machine called “The rack,” that is government inspected since they sell to the US Navy. I made a 10’ foot long 1/4” inch Dyneema test rope with eye splices at both ends and watched as the digital dial of the machine stretched the line past 2,000 lbs, and expected to see a splice break any moment. At 4,000 lbs., the rope looked as stiff as iron bar then finally at an incredible 7596 lbs the actual rope snapped with a dull thud, yet both my splices held. This was good enough for me, and I have an official test  certificate to prove it.

certificate to prove it.

I decided to replace the lifelines with Dyneema in blue.

After the new lifelines were fitted there was one final thing to do: Since the only thing that can weaken Dyneema lines is chafe, I decided to enclose the upper lines with plastic covers that clip completely over the rope and act as chafe guards. One of the areas where chafe is likely is where it passes through stanchions and these plastic pipes slide through Britannia’s stanchion holes yet still allow the rope to move freely inside. If any of the guards show signs of chafe from ropes or other sources it will be a simple matter to replace one section before it wears the lifeline itself. The covers also increase the line thickness that makes holding the lines much more comfortable.

Britannia’s finished lines now look very stylish and purposeful and I am confident that in the event of a real man overboard emergency I will have the least possible obstructions to get the person back up the side of the boat, past the lines.