When you own a boat anywhere along the southern and eastern coasts of The United States, you become acutely aware of the hurricane season from June to December. Some of these storms have a devastating effect, not only on boats but property and life itself. It is not surprising that boat owners usually have an app’ on their computers or phones linked to the principal United States authority on hurricanes, The National Hurricane Center (NHC), in Miami, which is part of The Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, (NOAA). The NHC issues very detailed charts and information from the beginning of the Atlantic storms season, along with analysis of weather systems that might turn into hurricanes of varying severity. (www.nhc.noaa.gov) Florida is the southernmost leading edge in the United States to be effected by hurricanes. Britannia was in a marina halfway up the Florida coast at Cape Canaveral, being the nearest port to my home in Orlando.

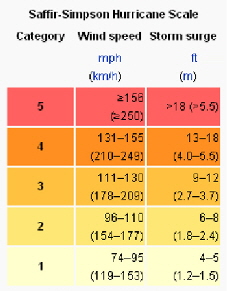

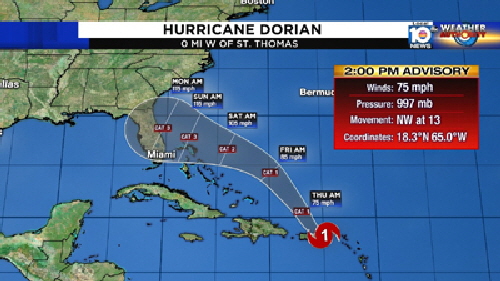

Hurricanes are categorized in five levels on what is known as the Saffir-Simpson hurricane scale, similar to the Beaufort scale that is so well known to yachtsmen. The big difference is that the Saffir-Simpson scale starts where the Beaufort scale leaves off at force 12! Anyone who has been at sea in anywhere near these winds knows it is difficult to even stand up and practically impossible to work on deck. The top hurricane level, number 5 has sustained winds starting at 155 mph! That's twice the velocity of a force 12! and really unimaginable or unsurvivable. Thankfully there have not been many of that strength that have made landfall anywhere on the North Atlantic path that storms usually followm from the bottom of the Caribbean northwards known as “Hurricane alley.” The last one was Katrina in August 2015, that crossed Florida as a category one killing 14 people then strengthened considerably in the warm waters of the Gulf of Mexico and smashed into New Orleans as a five, killing some 1800 people. It's therefore hardly surprising that I was concerned in September 2019, as a monster hurricane was working it's way up the Caribbean chain of islands and reported to make landfall as a category 3 on the east coast of Florida, guess where, Cape Canaveral! It was named Dorian.

These storms do change directions, and anyone with a television will have seen the incredible devastation and loss of life as Dorian roared into the low lying Northern Bahamas, reducing these pristine tropical islands into landscapes reminiscent of Hiroshima after the bomb. At the time the storm was hardly moving at 2 mph and lingered for two whole days as though wondering who to smash into next. The barometric pressure was 913 millibars and I had to tap my barometer on Britannia to see if it worked!

The following is a report from The NHC.

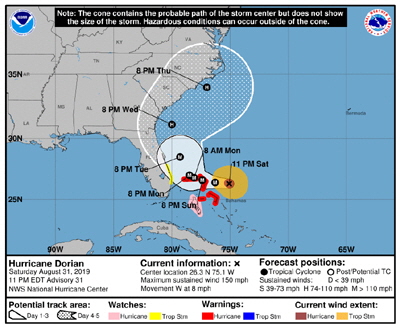

The center of Hurricane Dorian, at 01/1200 UTC, is near 26.5N 76.5W. This position is about 35 nm/ to the east of Great Abaco Island in the Bahamas, and about 225 nm to the east of West Palm Beach in Florida. Dorian is moving W, or 275 degrees, 8 knots. The maximum sustained wind speeds are 160 knots with gusts to 170 knots. Dorian is a Category 5 hurricane. The estimated minimum central pressure is 927 millibars. Numerous strong convection is within the center in the E semicircle, and within 60 nm of the center in the W semicircle. Scattered moderate to isolated strong rain showers are elsewhere from 21N to 30N between 70W and 78W. When Dorian decided to get moving again the NHC predicted it would make a sharp turn to the right, then work its way up the eastern side of Florida. From previous experience I had great respect for The NHC’s forecasting but this sharp turn seemed implausible that such a lumbering tempest 150 miles wide and packing winds of 150 miles per hour around a 20 mile wide eye could possibly turn anywhere. But turn it did on a WNW course and began rumbling straight towards the promontory so well known for space rocket launches. At its ongoing speed we had about two days to do the best we could to secure Britannia that was lying in a marina on the barge canal, just west of the actual port of Cape Canaveral. I now have even more respect for the NHC.

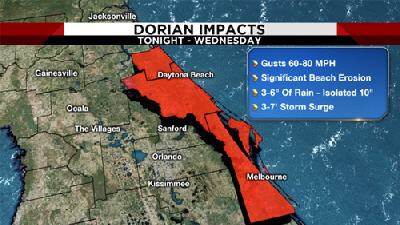

When Dorian decided to get moving again the NHC predicted it would make a sharp turn to the right, then work its way up the eastern side of Florida. From previous experience I had great respect for The NHC’s forecasting but this sharp turn seemed implausible that such a lumbering tempest 150 miles wide and packing winds of 150 miles per hour around a 20 mile wide eye could possibly turn anywhere. But turn it did on a WNW course and began rumbling straight towards the promontory so well known for space rocket launches. At its ongoing speed we had about two days to do the best we could to secure Britannia that was lying in a marina on the barge canal, just west of the actual port of Cape Canaveral. I now have even more respect for the NHC.

My wife Kati and I knew we were in for a hammering when NASA started moving a 200 foot high rocket launch gantry indoors into their gigantic vehicle assembly building at the Kennedy Space Center, only 10 miles to the north. If they thought Dorian might blow a massive rocket launching platform over, what chance would poor old Britannia  have?

have?

I was thankful I had renewed Britannia’s comprehensive insurance to include named hurricanes. My British registered schooner was previously insured through Lloyd's, but last year they decided to exclude named storms in Florida so I switched to a company that would. There's not much point having insurance here if it doesn't cover hurricane damage, but it a’nt cheap. We began the process of preparing Britannia for what might well be the greatest test of her 38 year life

The last hurricane we weathered was a category 3, the center of which passed some 30 miles off the coast on its way north. This experience taught us that there are mainly two factors to consider: One is obviously wind strength, but the other is sea surge that the fierce wind pushes very high waves straight into the inlets to the intracoastal waterway. This surge raised the water level 4’ feet in the marina the boat was in at the time. This was “only” a force three hurricane and it stayed quite a long way offshore. The storm forecast to hit us in a few days sounded like it would be very different.

Port of Cape Canaveral has grown into a very busy place over the past decade, it is now the home of five major cruise lines, operating humongous ships that look more like floating apartment blocks many balconies high. It was therefore not one bit encouraging to learn they were all heading out to sea as fast as they could shove their passengers on board and changing their itineraries to steer well clear of Dorian. You can do this when you have a cruising speed of 22 knots and outrun a storm traveling at only about seven.

The port is open to the Atlantic ocean and therefore tidal, but at its westerly end is a massive 600 foot long lock designed to act as a tidal gate to the intracoastal waterway on the other side. I telephoned the lockmaster and it was disconcerting to learn that he thought this particular storm surge would probably rise above the lock gates that are eight feet above normal high tide! There are two tidal marinas inside the port and the lock was due to close in one day's time in preparation for the hurricane's arrival. Many small boats, along with a few big ocean fishing boats scurried through to the comparative safety from the sea surge to the intracoastal side. There would still be no shelter from the wind

As it shuffled northward Dorian thankfully decreased from a category 5 to a 3, but which is still a very dangerous storm, and continued on its relentless march up the coast. Evacuations were ordered from the outer banks all the way along Dorian's path and warnings issued that the high bridges, high enough to allow Britannia’s 57’ foot mainmast to pass beneath would be closed when the wind reached 35 mph. This precaution was to prevent high sided vehicles from being blown over and blocking the evacuation routes, or that they might even topple over the parapet into the intracoastal waterway as has happened before. Hurricane season is not the best time to be working in Florida at the best of times. We were operating in 95 degrees Fahrenheit with oppressive humidity.

We began by removing Britannia’s roller furling jib and both roller furled staysails to reduce windage high up the mast. The mainsail is in-mast furled so that was protected inside the mast - so long as the mast stayed upright that is. We then lowered the 22’ foot long yard that houses the squaresail inside it, and this was lashed on deck. All three booms were lowered to the deck and lashed to their sheet tackles to stop them from rolling around as the boat heeled in the wind. All hatch covers, the liferaft cover and windlass cover were stowed below. All mast lines that are normally belayed to pins on the pin rails were transferred to the mast and secured, thereby reducing rope windage. I taped up the Dorade and engine fan inlet vents on deck.

We began by removing Britannia’s roller furling jib and both roller furled staysails to reduce windage high up the mast. The mainsail is in-mast furled so that was protected inside the mast - so long as the mast stayed upright that is. We then lowered the 22’ foot long yard that houses the squaresail inside it, and this was lashed on deck. All three booms were lowered to the deck and lashed to their sheet tackles to stop them from rolling around as the boat heeled in the wind. All hatch covers, the liferaft cover and windlass cover were stowed below. All mast lines that are normally belayed to pins on the pin rails were transferred to the mast and secured, thereby reducing rope windage. I taped up the Dorade and engine fan inlet vents on deck.

We then removed the large awning that was folded and stowed below. The five part cockpit Bimini came of next, along with its support framework which was lashed down. A sail bag was placed over the pedestal to stop the instruments becoming soaked. I considered leaving the 10’ foot dinghy on its davits, but if the wind came from the north it could easily shake the dinghy to destruction. We deflated it and took it to my house in our SUV, along with our new 6 hp outboard motor.

The most important things were the mooring lines. Britannia weighs about twenty two tons and she was bow-to facing the dock and secured at the stern to two massive 12” inch diameter pilings. Most lines were 1” inch diameter three strand nylon and consisted of: fore and aft springs both sides; stern lines crossed from one pilling to the opposite cleat; bow lines going forward to dock cleats and aft to cleats on the finger docks; a line from the crance iron on the tip of the bowsprit to both sides of the dock that stopped the bow ranging about from side to side. There was only one way all these lines could be strengthened and that was to double them which I did! However, there was no more space on some of the dock cleats, so I secured the second lines to the sturdy posts beneath the dock. The lines in the photographs might appear somewhat loose, because we really expected a significant rise in the water level especially if the lock flooded, not to mention the horrendous rain that always accompanies strong hurricanes. This can be horizontal fire-hose pressure that can actually damage bare skin. If the lines were too tight and Britannia tried to rise with the water there would be an enormous strain on cleats and lines and something would eventually break. We did not plan on being there to adjust them as we would in a normal tidal moor, because even if we had decided to weather the storm aboard it is highly unlikely I would have been able to adjust anything in the height of the deluge. It was all pretty much guesswork and the extra ropes completed the outside work so we packed it in for the day, totally exhausted.

The most important things were the mooring lines. Britannia weighs about twenty two tons and she was bow-to facing the dock and secured at the stern to two massive 12” inch diameter pilings. Most lines were 1” inch diameter three strand nylon and consisted of: fore and aft springs both sides; stern lines crossed from one pilling to the opposite cleat; bow lines going forward to dock cleats and aft to cleats on the finger docks; a line from the crance iron on the tip of the bowsprit to both sides of the dock that stopped the bow ranging about from side to side. There was only one way all these lines could be strengthened and that was to double them which I did! However, there was no more space on some of the dock cleats, so I secured the second lines to the sturdy posts beneath the dock. The lines in the photographs might appear somewhat loose, because we really expected a significant rise in the water level especially if the lock flooded, not to mention the horrendous rain that always accompanies strong hurricanes. This can be horizontal fire-hose pressure that can actually damage bare skin. If the lines were too tight and Britannia tried to rise with the water there would be an enormous strain on cleats and lines and something would eventually break. We did not plan on being there to adjust them as we would in a normal tidal moor, because even if we had decided to weather the storm aboard it is highly unlikely I would have been able to adjust anything in the height of the deluge. It was all pretty much guesswork and the extra ropes completed the outside work so we packed it in for the day, totally exhausted.

We were planning to leave the following day, but it still took time to removed our many personal possessions on Britannia, in case she actually sank. We removed five paintings, including one of Nelson, (every British sailors hero), in a beautiful gilt frame. I also had two ship models I had made years ago, one a half section of Victory and the other a scale model of Sir Winston Churchill, the Sail Training Accociation’s schooner that I had actually sailed on. All our clothing was packed including oilies and lifejackets. All food stores were removed in five heavy bags. Finally, the ship's papers and information leaflets on every bit of equipment came off. All these things were crammed into our van, roof high to the point that I could not see through the rear mirror.

We were planning to leave the following day, but it still took time to removed our many personal possessions on Britannia, in case she actually sank. We removed five paintings, including one of Nelson, (every British sailors hero), in a beautiful gilt frame. I also had two ship models I had made years ago, one a half section of Victory and the other a scale model of Sir Winston Churchill, the Sail Training Accociation’s schooner that I had actually sailed on. All our clothing was packed including oilies and lifejackets. All food stores were removed in five heavy bags. Finally, the ship's papers and information leaflets on every bit of equipment came off. All these things were crammed into our van, roof high to the point that I could not see through the rear mirror.

That day, the last before the full effect of Dorian was expected, an evacuation was recommended from the outer shores of Cocoa Beach on which the City of Cape Canaveral stands and a curfew would be imposed that night between 11 pm and 6 am. Dorian was about 100 miles south and expected to hit that night and early the next day. As a final safety measure I disconnected both shore power lines along with the shore water hose. The only things that was now operational on the whole boat were the two automatic 12 volt bilge pumps.

As I stepped off Britannia I couldn't help stroking her bowsprit and telling her that we would be back as soon as we could, but I still felt a coward leaving her to fend for herself. A few people who lived on their boats decided to sit it out rather than go into one of the crowded shelters opened on the mainland. We wished them well and exchanged phone numbers, just in case…

As I climbed into the driver's seat Kati suddenly said "We've forgotten the windmill." She was talking about the KISS wind generator high up the mast, and how in previous storms I had unscrewed the vanes and lowered them down. "I can't go up there now. We'll just have to hope for the best." I replied and shifted into gear. As we drove 80 miles west to Orlando the winds buffeted our van and ominous black clouds could be seen on the southern horizon.

The good news was that Dorian had wobbled a little to the east, away from the coast. Wobble is actually an official NHC term for a slight but not always permanent course change. But it still gave the Cape area a whopping swipe with winds in the 100 to 130 mph range and the aforementioned torrential rain. As luck would have it the sea did not breach the lock so the water level in our marina only rose about 15” inches

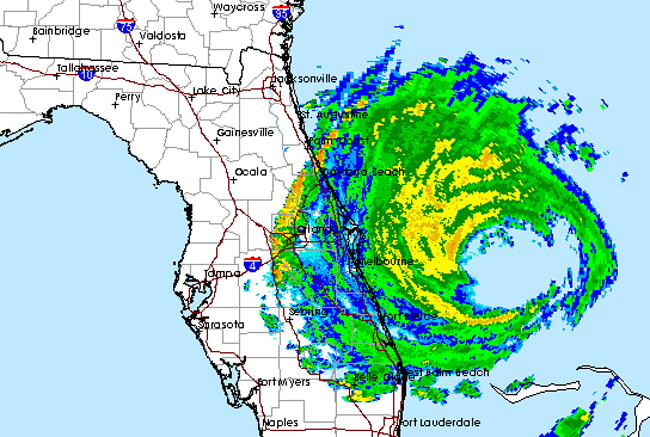

At our home we were glued to local television reports that showed a radar picture of Dorian about level with Cape Canaveral. There were also images of roofs being torn off houses and factories and less well-built fabricated homes being completely wrecked, sometimes one house flying off its foundations and smashing into its neighbor. There were also reports of tornadoes. These are sudden bursts of very high local winds as much as 200 mph spinning off the anti-clockwise rotation of the main storm. Thankfully and in gratitude to the excellent forecasting and warnings from the NHC, there were no reports of deaths, but plenty of injuries. Big old oaks were down and roads blocked everywhere.

We returned to Britannia on the second day with Dorian well to the north, having caused severe flooding as it smashed into the small outer bank town of Ocracoke in North Carolina. Britannia looked a little bedraggled, but otherwise she was fine with no damage above or below decks and the vanes on the windmill were still there. Dorian continued as a category 2 hurricane all the way up to Newfoundland and Nova Scotia and was last heard of heading west, towards the coast of Ireland and Scotland.

We decided to leave Britannia in her stripped condition on deck, with the extra lines in place ready for the next big blow, because there surely would be one. We will never know how much our hard work preparing the boat for the storm resulted in the lack of damage. Many boats nearby had their sails blown out because they were not removed. A few Bimini's were also damaged and one boat sank.